The role of green infrastructure in mitigating the impacts of weather- and climate change-related natural hazards

Introduction

Natural resource scarcity, climate change impacts, continued employment crises, public budget debts and economic recovery plans are some of the challenges currently faced by governments in Europe. Moreover, Member States in the European Union (EU) need to continue building or rebuilding roads, sewage systems, levees, etc. (also known as grey infrastructure).

Despite being essential for economic growth, investments in such infrastructure are significant and put heavy burdens on governments. But as governments debate the future of economic growth and sustainable development, there is one infrastructure solution that can provide a good return on investment: nature.

In the past, governments and other investors automatically looked to expensive traditional grey infrastructure solutions in order to solve problems. Now, new and in many cases cheaper approaches are emerging that use natural processes or GI rather than concrete and steel. Forests, wetlands and other natural ecosystems are not commonly considered forms of infrastructure. But they are. Forests, for example, can prevent pollutants from entering streams that supply fresh water to cities and businesses downstream. Upstream landscape conservation and restoration measures can act as natural water filtration plants, as an alternative to more conventional water treatment technologies. As such, they are a form of GI that can serve similar functions to grey infrastructure.

GI solutions that boost disaster resilience are also an integral part of EU policy on disaster risk management. Climate change and infrastructure development make disaster-prone areas more vulnerable to extreme weather events and natural disasters such as floods, landslides, avalanches, forest fires, storms and wave surges that cause loss of life and result in billions of euros of damage and insurance costs each year in the EU. The impacts of such events on human society and the environment can often be reduced using GI solutions.

The full report can be downloaded from the right-hand column of this page.

Key Messages

- In many cases, Grean Infastructure (GI) solutions are less expensive than grey infrastructure, and provide a wide array of co-benefits for local economies, the social fabric and the broader environment.

- Making the financial case for GI is complicated: it can be difficult to make a valid comparison between GI and grey infrastructure with a focus on incurred expenses and benefits. We know that GI solutions often provide multiple benefits (noise reduction, increased carbon sequestration, recreation opportunities, clean water, etc.) that are often cheaper and more robust, not to mention more sustainable, both economically and socially (EEA, 2014). These multiple benefits should be captured in the equation as having positive spin-off effects, while grey infrastructure solutions typically only fulfil single functions such as drainage or transport.

- Think about green before investing in grey: planners should compare green to grey and identify new opportunities for investing in nature, including a combination of green and grey approaches when nature-based solutions alone are insufficient. Many countries in the EU have already taken this on board and have prepared national guidance documents and/or strategies to actively encourage investments in GI as an essential part of sustainable spatial planning. The importance of GI is also recognised in the EU policy domain.

- The impacts of extreme weather and natural disaster events on human society and the environment can often be reduced using GI solutions. For example, functional flood plains, riparian woodland and protection forests in mountainous areas, barrier beaches and coastal wetlands can be set up in combination with disaster reduction infrastructure such as river protection works. Investment in ecosystem-based DRR and GI can thus provide many benefits for innovative risk management approaches, adapting to climate change-related risks, maintaining sustainable livelihoods and fostering green growth.

- If risk and demand are high, and ecosystem service capacity for risk mitigation is low, then ecosystem restoration clearly presents a significant and cost-efficient improvement for disaster risk mitigation. However, it should be noted that besides anthropogenic reasons, there are often also natural reasons explaining why a specific area cannot supply relevant ecosystem services.

- Cities and local authorities are the first to deal with the immediate consequences of such disasters. They therefore play a critical role in implementing prevention measures like GI.

The Report

To address some noted challenges and information gaps, the report (download available in right-hand column) tries to demonstrate the role of GI for mitigating vulnerability to weather and climate variability-related natural hazards at European level. It proposes a simple, practical methodology for screening (rather than assessing) ecosystem services in areas where GI may contribute to reducing current (or future) weather- and climate-related natural hazards. The report addresses landslides, avalanches, floods, soil erosion, storm surges and carbon stabilisation by ecosystems.

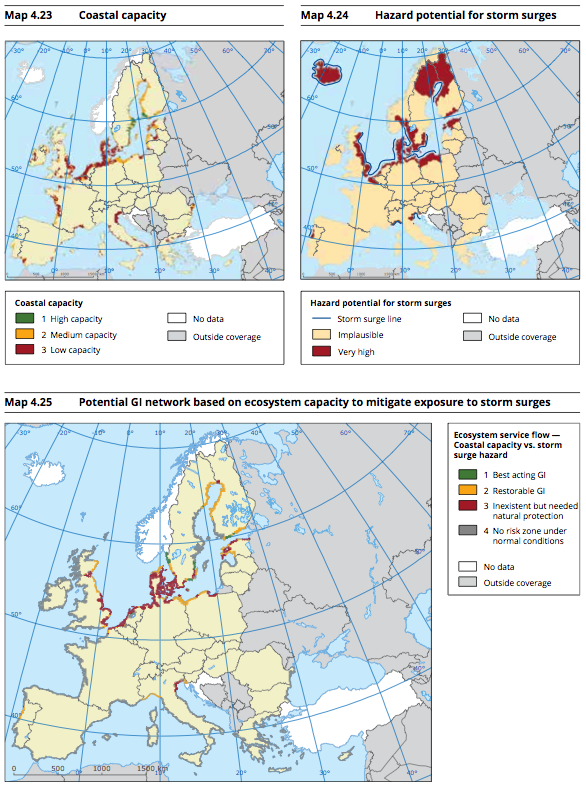

In the study, GI is defined by its capacity to provide a relevant number of ecosystem services. The maps presented in the study (see Figure 1 above for an example) provide an overview of where specific weather- and climate-related natural hazards are likely to occur, where well-functioning ecosystem services exist which can support DRR and climate adaptation so as to lessen the impacts of natural hazards (e.g. floods and landslides), and where the provision of ecosystem services may be improved.

Outcomes and Impacts

Regions with well-functioning ecosystem services (depicted in green in the maps -available in the report) are considered to be part of a GI network that has the main role of mitigating the impacts of climate change natural hazards and/or supporting adaptation to climate change impacts. Those regions exhibiting a lack of mitigating ecosystem services should be considered priority areas for investment in or restoration of the required services, as there is a demand for them expressed by the presence of a natural hazard and assets at risk.

The study identifies two different levels of lack of GI:

- areas with no or a very low capacity of relevant ecosystem services for the mitigation of a given natural hazard (mapped in red);

- areas with existing ecosystem services that are not able to function at full capacity (mapped in orange).

For each of the natural hazards assessed in this study, an individual European-scale map of potential GI elements and restoration areas has been produced. For potential restoration areas, stakeholders are requested to take a decision on which areas are to take priority, i.e. whether to restore the partially functioning ones or the non-functioning ones. For example, restoring areas with no relevant ecosystem services for the mitigation of a given natural hazard (mapped in red) might reduce hazard considerably if they are located in an area where the hazard is present.

These decisions might be further supported by considering the demands of population and infrastructure for protection by GI. An additional series of maps has been produced for this purpose at the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) 2 level. These maps define ‘high-risk areas’ at locations where high demand matches with low/ medium-quality GI networks, and where medium demand matches with low-quality GI networks. Such areas are potential priority areas for GI restoration.

For future research, it is proposed that the outlook of GI be expanded: from being based on ecosystem services alone, to include other topics such as protected lands, sensitive areas or natural assets as a cornerstone of GI networks to be developed.

Authors & Acknowledgements

The report (download in right-hand column) was managed and prepared by the European Environment Agency (EEA) (Gorm Dige) and the European Topic Centre on Urban, Land and Soil systems (ETC/ULS) (Stefan Kleeschulte, Christopher Philipsen, Stefan Schindler and Gabriele Sonderegger). Comments and input were also provided by the European Topic Centre on Climate Change Impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation (ETC/CCA)(Jaroslav Mysiak).

Suggested Citation

EEA, 2015, Exploring nature-based solutions: The role of green infrastructure in mitigating the impacts of weather- and climate change-related natural hazards, EEA Technical report No 12/2015, European Environment Agency

(0) Comments

There is no content