Adaptation and Gender in Bangladesh: NCAP Case Study

Women’s Vulnerability to Natural Disasters in Noakhali

In Noakhali, society supports a rigid gender division of labor that perceives men and women’s roles differently and distinctly defines women’s mobility, duties and responsibilities. The traditional family model and gender roles in Noakhali are changing very slowly. However, due to extreme poverty and the increased inability of families to provide protection for their women, there is an increased mobility of rural women in economic activities when previously women would have stayed at home. Other than the Pourashava areas and some urban areas, the gender roles imposed by society are usually considered ‘natural’.

Gender Division of Labor:

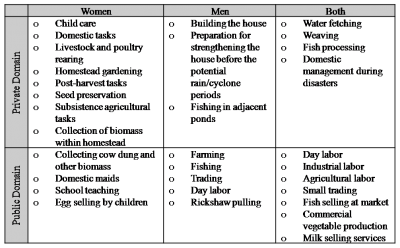

In Noakhali women’s positions are rooted in their social traits, patriarchy and gender division of labor. Men’s activities are considered as income generating, while women’s activities are mostly limited to the domestic domain. The table depicts the gender division of labor in Noakhali as revealed during focus group discussions with both men and women.

Gender Division of Labor

Wage Rate

Today, though not comparable with their male counterparts, women are participating in the labor market, but there exists high wage rate disparities between men and women. Wage rates are different over different seasons, depending upon the demand for labor. In rural areas the wages reach their peaks during the transplantation and harvesting periods of main crops (such as T. Aman). In char areas the wage differences are even greater.

Access to Resources

Women’s access to resources in Nakhali is mostly confined to the domestic domain (domestic utilities, cattle, homestead and adjacent ponds), it is often only when they go to fetch drinking water from a distant tubewell that they leave the domestic domain. Some women have inherited landholdings (either from their father, or in case of widows from their husband), but in most cases the women do not have the right to make decisions on the usage of these resources, whether to retain them and how to use them, or to sell them. Social expectations, family values and laws all affect women’s access to common property resources, infrastructure and formal and non-formal institutions. Women’s claim on household resources is also secondary to men’s which undermines their contributions to sustainable livelihoods.

In terms of access to financial resources, hardly any women in Noakhali go to the Krishi Bank or other banks and apply for loans. Only non-governmental organisations (NGOs) sometimes support them with micro-credit, although this is still uncommon. It is the norm that the male member of the household (father, husband, brother) has the control over this money andyway, so it is difficult to assess whether the increased access to borrowing from NGOs alone can improve women’s access to financial resources or enhance their participation in private/family decision making processes. The question of who controls the resources is vital.

Access to Health Care, Safe Water, and Sanitation

It is mainly women who take the responsibility for collecting water. Those households that do not possess tubewells have to fetch water from distant households, adjacent schools, madrasas, the district board office etc. Women and childrens face tremendous problems collecting drinking water all year round. It is often dangerous when women have to go outside for water at night. There is also a risk of arsenic poisoning and people do not use those tubewells on which the Department of Public Health Engineering (DPHE) has put red marks.

The health of women, especially those who live in char areas, is in a poor state. Many women never visit a doctor in their lives and their attitude towards medication is negative. Most of the women in char areas would not consult a doctor unless there was a severe emergency. In the case of childbirth, almost every family prefers delivery at home with the help of their female relatives. The sanitation situation is very poor; almost every house in char areas uses a kutcha latrine which is unsanitary. According to these people, sanitation is the most neglected area for them.

Social Insecurities in Char Areas

The construction of embankments (beribadh) is a symbol of both environmental and social security for the people of char areas although people living on and outside beribadh are less secure than the people living within them. People outside the embankments are often attacked by local terrorists. When women have to go outside for various purposes like fetching water etc. they feel unsafe. People outside the embankments tend to be poorer as they are more vulnerable to disasters without the protection that those living inside the embankments have.

Back to:

Netherlands Climate Assistance Programme (NCAP)

Methodology of Bangladesh NCAP Project

Key Finding from NCAP Bangladesh project

On to:

(0) Comments

There is no content