Mitigation and Adaptation in the UNFCCC Debates

Introduction

Climate Change Adaptation appears to occupy the center of the climate negotiations. There are claims in the literature on climate diplomacy about an ‘adaptation turn’ in the last years of the negotiation. We challenge those and find adaptation to have been present and highly visible from the very beginning, particularly the specific question of adaptation finance. In the larger debate on climate change, the notion of ‘adaptation’ is often opposed (or at least contrasted) to that of ‘mitigation’. Such a contrast is not without reason. The two notions refer to vastly different ways to deal with global warming. ‘Mitigation’ refers to the efforts to lessen the impacts of climate change by acting on its causes and therefore reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG). ‘Adaptation’, on the contrary, refers to the efforts to prepare our societies to cope with the effects of climate change. Though the two approaches are not mutually exclusive (there is no contradiction between striving to avoid the dangers and prepare to deal with those that cannot be avoided), they have often been opposed by the actors in the climate change debate. In this narrative we explore the status of mitigation and adaptation in the UNFCCC debate.

This article is part of the Climaps project by EMAPS. If you want to learn more about the project, please read more inthis article.

The rise of adaptation related issues

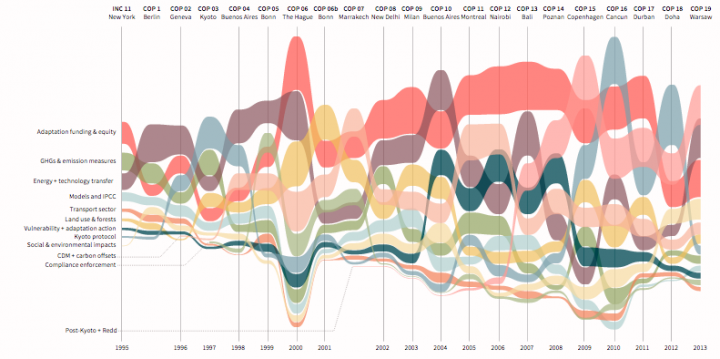

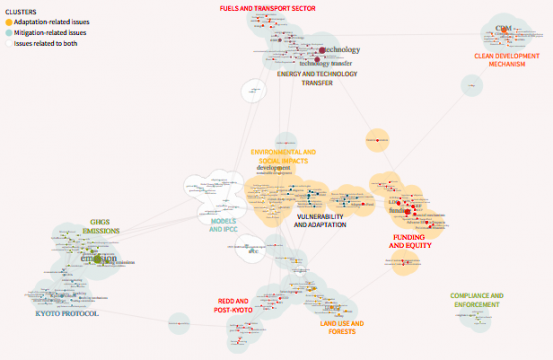

Looking at figure 1 below, the difference between mitigation and adaptation is evident. Terms related to the efforts to mitigate climate change organize 7 of the 12 clusters of the networks, grouped in three main semantic arenas, widely scattered across the graph (‘emission reduction’; ‘carbon sinks’; ‘energies, technology transfer and clean development projects’).

Compared to the mitigation clusters, adaptation clusters are fewer and more compact. The 3 clusters dedicated to adaptation (‘environmental and social impacts’, ‘vulnerability and adaptation’ activity and adaptive ‘funding and equity’) are tightly grouped at the centre of the map. This shows the difference in status of adaptation in the UNFCCC negotiations.

Where mitigation is the primary objective of the conference, and thus formulated in numerous ways, adaptation, impacts and vulnerability seem more limited in their articulation, but also more commonly connected to other issues (which accounts for their centrality in the map). The figure also reflects the different types of contextualisation of climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Figure 1: from Climaps.eu.The ‘place’ of adaptation. Network of terms co-occurring in the same paragraphs of the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Volume 12. Node position is determined by a force vector algorithm (Jacomy et al., forthcoming) bringing together terms directly or indirectly linked, and keeping away terms with fewer co-occurrences. Node size is proportional to their frequency in the corpus. Node color follows the clusters identified by the clustering algorithm. Click to see main Issue map.

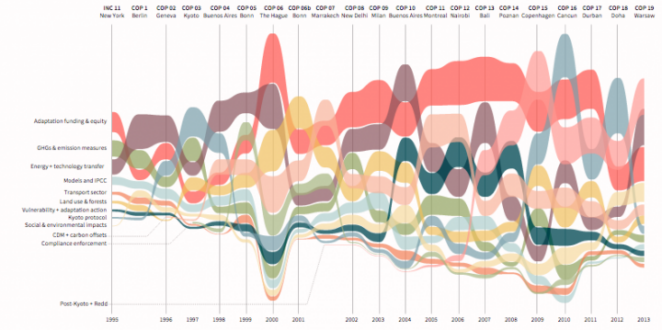

Looking at Figure 2, one will immediately notice that there is (with the exception of COP6 in the Hague) a general increase of the overall number of appearances of issues until COP16 in Cancún. This reflects the increase of the total number of participants during the COPs.

Adaptation and mitigation issues are both visible in the UNFCCC negotiations. However mitigation has been from the very beginning a top priority on the negotiations’ agenda. In the first phase of the negotiations little attention was dedicated to the actions of developing countries to cope with the impacts of climate change. Except that the most vulnerable members succeeded in putting the issue of financing adaptation activities on the agenda from the first COP (see also figure 4).

Adaptation, however, assumed greater importance in the second phase of the negotiations. With all parties facing difficulties in achieving their mitigation objectives, debates on what shall be done regarding vulnerability, climate change impacts and adaptation, as well as how to finance these actions became more relevant.

Figure 2: from Climpas.eu. Stream graph of the absolute and relative visibility of issues during UNFCCC negotiations, 1995-2013. The size of each flow is proportional to the number of paragraphs in which two terms defining the issue are present. Flows are sorted according to the number of occurrences: for each COP, the highest flow corresponds to the most visible issue while the lowest corresponds to the least visible. Click to see Issue map.

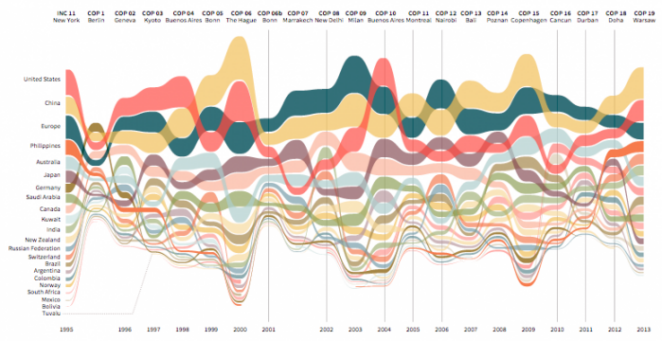

The diagram (Figure 3) shows a remarkable stability. Most countries maintain their relative rank throughout the 19 COPs. The 10 most active countries are represented by a rather stable, small group, which includes the United States, China, Europe, Australia, and Japan. The three leaders of the negotiations – China, the United States, and Europe – are ubiquitous. There are several exceptions. First, the Philippines and Bolivia, two countries from the southern hemisphere, have taken on very active roles, perhaps disproportionate with their size.

Figure 3: from Climaps.eu. Stream graph of the absolute and relative visibility of the countries of the UNFCCC negotiations, 1995-2013. The size of each country flow is proportional to the number of paragraphs in which the name of the country appears. Flows are sorted according to the number of occurrences: for each COP, the highest flow corresponds to the most visible issue while the lowest corresponds to the least visible. Click to see main Issue map.

Key messages

– Reading the two maps (Figures 1 and 2) together, it is possible to remark that (as expected) mitigation plays a preeminent role in climate diplomacy. Mitigation constitutes the bulk of UNFCCC’s discussions.

– Adaptation appears to occupy the center of the climate negotiations and has been present and highly visible from the very beginning (especially with the topic of adaptation funding). These findings challenge some of the claims in the literature about climate diplomacy about an ‘adaptation turn’ in the past few years of the negotiation.

– What has always been present and visible in the negotiations is not the entire discussion about adaptation, but the specific question of adaptation finance.

– No clear pattern exists to support the hypothesis that certain states or groups of states may be particularly active on adaptation related issues.

The maps were produced by analyzing the reports on the UNFCCC’s discussions provided by Volume 12 of the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

More about this project

(0) Comments

There is no content