An Introduction to green bonds

Introduction

Finance is an important enabler for adaptation, for both developed and developing countries. It can be delivered through a range of instruments including grants or subsidies, concessional and non-concessional (ie. market) loans as well as other debt instruments, equity issuances (listed or unlisted shares) or can be delivered through own funds, such as savings (New et al., 2022, 2586). It can come from international actors, such as multilateral development institutions, regional development banks, other financial institutions, national government funds, as well as private stakeholders, such as foundations, companies, individuals and real estate developers. For further information see the introduction to Financing Urban Adaptation.

A green bond is a debt financial instrument and “is issued to raise capital specifically to support climate related or environmental projects.” (World Bank, 2015). It is promoted as a promising option for commercial debt finance towards climate-resilience-related efforts, including adaptation. Compared to other financial instruments, such as equity, green bonds are considered a lower –risk investment because they have a fixed rate of return.

A traditional bond, alternatively called a vanilla bond, involves an issuer selling the bond to an investor, with the promise to repay the principal debt plus a premium when the bond matures. The structure of a green bond is the same as that of a conventional one except that the proceeds of the green bonds are used exclusively to finance projects that deliver environmental benefits. A green bond issuer needs to include “use of proceeds” clause in the process, which can be understood as allocation of funds for green projects (Tuhkanen, 2020).

Another important distinction to make is the one between a green bond and a climate bond. There are many similarities between the two, including their association with climate finance and mobilising private climate finance (Rosembuj & Bottio, 2016). However, unlike those of green bonds, the proceeds of climate bonds are used exclusively to finance projects that address climate change, such as for reduction of carbon emissions or adaptation to climatic shocks (Mackenzie & Ascui, 2009).

Projects meeting green objectives can fall within the broader range of categories (ICMA, 2021):

- Renewable energy

- Energy efficiency

- Pollution prevention and control

- Environmentally sustainable management of living natural resources and land use

- Terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity

- Clean transportation

- Sustainable water and wastewater management

- Climate change adaptation

- Circular economy adapted products, production technologies and processes

- Green buildings.

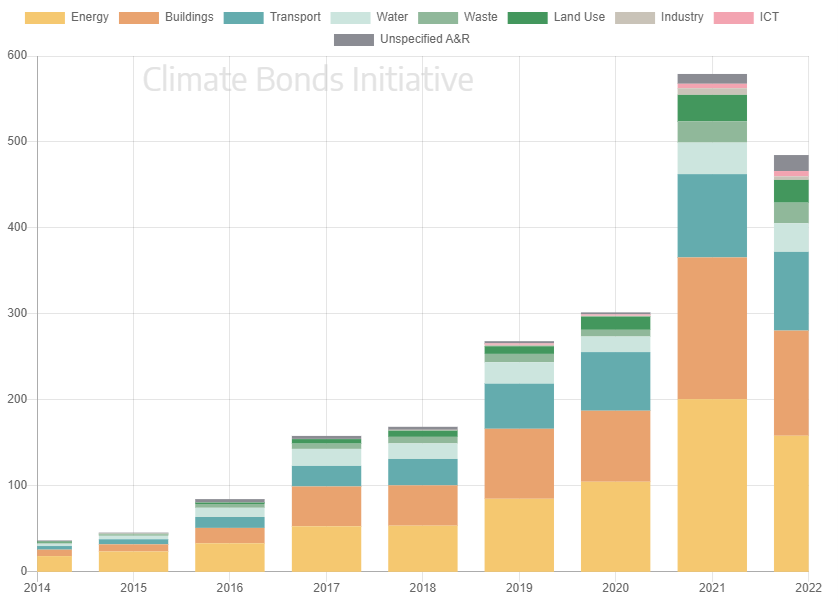

Energy, buildings and transport traditionally remain the largest use of proceeds categories (Fig. 1).

Use of proceeds green bonds constitute the largest share of the market while there are multiple other types utilised by different issuers (Tab. 1). Green bonds issuance can take place at different levels (Global Climate Action Partnership, 2023):

- Supranational green bonds are issued by international organisations to fund green projects across multiple countries. For example, through NextGenerationEU Green Bonds Programme, the Commission makes one of the largest green bond transactions.

- Sovereign green bonds are issued by national governments to direct monetary flows towards environmentally sustainable investments. Sweden’s sovereign green bond issued to allocate funds to maintain the railway system, as well as develop fossil-free steel production.

- Sub-national green bonds are issued by local governments, including cities, states, provinces and others to raise funds for green initiatives implemented locally. DC Water, the water and wastewater utility of the United States issued its inaugural green bond to finance the DC Clean Rivers Projects, including water quality restoration, flood mitigation and biodiversity conservation activities.

- Corporate green bonds are issued by corporations to meet their environmental objectives, frequently related to reducing their carbon footprint. Iberdrola, a Spanish electric utility company, has used green debt financial instruments to fund renewable energy projects.

| Type | Feature | Example |

| Use of proceeds bond | Funds are earmarked for green projects | EIB Climate Awareness Bond, Barclays Green Bond |

| Use of proceeds revenue bond | Funds are used to finance or refinance green projects. Issuer’s revenue streams from fees, taxes etc. are used as collateral to back the security | Hawaii State bond – backed by electricity tariffs of the public utility |

| Project bond | Funds are earmarked for specific underlying green projects | Invenergy Wind Farm bond |

| Securitisation bond | Funds are used to finance or refinance green projectsPools a large number of similar financial assets, such as mortgages, which are then used as collateral to back the security | Obvion bond backed by green mortgages |

| Covered bond | Funds are earmarked for eligible green projects included in a cover pool. The cover pool includes assets that are set aside to provide security for bondholders in case of the issuer’s bankruptcy | Sparebank 1 Bolligkredit green covered bond |

Green Bonds Ecosystem

There is no internationally agreed framework for issuing green bonds although there are various regulatory initiatives on different levels, including international standards, regional guidelines and national legal frameworks. This could be seen as an emerging ‘ecosystem’ for enabling green bonds.

Green Bond Principles developed by the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA, 2021) provide a framework to ensure transparency and integrity of the information flow between issuers and other stakeholders through four key components, including use of proceeds, project evaluation and selection process, management of proceeds, as well as reporting. The Climate Bonds Standard and Certification Scheme, developed by the Climate Bond Initiative (CBI, 2023), is used internationally by issuers, governments and investors to maintain credibility of the instrument and support investment decisions aligned with the good environmental practices.

Regional initiatives to create a conducive enabling environment for green bonds instruments are taking off in different parts of the world. To support it’s European Green Deal, the Commission is establishing an EU Green Bond Standard, which is still work in progress. Following the policy making timeline, in 2023, a political agreement on the EU Green Bond Standard was reached. ASEAN Green Bond Standards also aim to support the member countries in standardising rules for green bonds (ACMF, 2017).

National green bond frameworks and guidelines are appearing in different countries, including but not limited to China, India, US, France, Germany, Kenya, UAE and others, and are usually part of broader sustainable finance strategies. For instance, Kenyan Sovereign Green Bond Framework was put together as part of the government’s plan to finance country’s updated Nationally Determined Contribution 2021-2026, as well as to fund the post Covid-19 budget deficit following green and resilient recovery principles. The framework was developed in a consultative process, including public and private sectors, as well as academia, civil society and development partner institutions. It was designed to align with other international and regional frameworks, including the ones mentioned above (Republic of Kenya The National Treasury and Planning, n.d.).

Market Overview and Outlook

Despite 2022 capital markets activity being hit by geopolitical shocks, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the green bond market has been witnessing steady exponential growth since market inception in 2007. The estimated average annual growth rate in the period of 2007-2020 was 95% reaching a cumulative issuance of USD 1 trillion. The first green bond was issued by multilateral institutions, such as European Investment Bank and the World Bank. This was followed by the first corporate green bond in 2013 and the world’s first sovereign green bond in 2016. Geographically they are still concentrated in developed countries with the markets in most developing nations still being in a nascent state (CBI, 2022).

However, the future development of green bonds, both in developed and developing countries may depend on the ‘signal’ (or lack of) that the capital markets need from policy/governments to induce them to align investment strategies with climate goals (Kreibiel et al., 2022).

Challenges

Despite registered market growth, growing popularity among different stakeholders, and increasing evidence of potential of the instrument, there are a number of challenges that need to be addressed.

- Additionality: there is a concern whether the green bonds are leading to additional climate financing as some of the interventions financed by the instrument would have happened regardless.

- Standardisation: lack of internationally agreed standards and uniform disclosure requirements can question the financial sustainability of green bonds linked to their ability to generate return. The wide range of certification schemes globally with no universal framework or monitoring and reporting lead to lack of harmonisation of disclosure requirements and the use of proceeds (Weber and Saravade, 2019).

- Greenwashing: the voluntary nature of certifications and the absence of clarity regarding what classifies as green leads to the risk of greenwashing, with green bonds being used to fund non green interventions such as fossil fuel powered utilities. For instance, the $500 million green bond issued by Exim bank of India was partially used to finance a railway line to supply coal to the notorious Rampal coal plant of Bangladesh – the proposed location of which was in proximity of the Sundarbans Mangrove forests (Brightwell, 2016).

- Inequity: power, resources and capacity imbalances between developed and developing countries become a hindrance for the latter to successfully mobilise the much-needed investment. Capital marketsof developing countries are often underdeveloped, equity based, and lack debt instruments, which impedes proliferation of green bonds. Knowledge gaps and lack of technical expertise act as impediments to proper monitoring and assessment of the proceeds of green bonds to ensure their alignment with the Green Bond Principles (Banga, 2018). Inadequate institutional support, particularly due to lack of collaboration between different ministries that have different priorities often slows down the process of issuance of green bonds and sets back market development. High transaction costs associated with getting green bond certification, particularly when it needs to be proven that the bond issuer is creditworthy is a major barrier (Tuhkanen, 2020).

Conclusion

While green bonds have potential, an appropriate ecosystem is needed to ensure their efficacy in the context of both developed and developing nations, as well as a clear policy signal. Appropriate guidelines or rules and regulations for listing of green bonds, more efficient disclosures via credible certification, reduced issuance cost through tax incentives, improved policy support and coordination to build capacity of financial institutions, and awareness raising for environmental and social investments can help catalyse this nascent market and make green bonds play a more effective role in addressing climate financing needs, including adaptation, especially of vulnerable nations.

References

- ACMF. (2017). ASEAN Green Bond Standards. https://www.sc.com.my/api/documentms/download.ashx?id=75136194-3ce3-43a2-b562-3952b04b93f4

- Banga, J. (2019). The green bond market: a potential source of climate finance for developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 9(1), 17-32. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/20430795.2018.1498617?casa_token=DIfsJfOTC7EAAAAA:73vko1epPVJ1RapC4VFB4F3bPupEAArd-Qvbzp-sOsAskt2YXY4mwdJmQ8k-WGjyK0yySwdg6ZM

- Brightwell, R. (2016). How Green Are Green Bonds?. Climate2020, 12.

- CBI. (2023). The Climate Bond Standard. https://www.climatebonds.net/standard/the-standard

- Global Climate Action Partnership. (2023). The green bond roadmap. https://globalclimateactionpartnership.org/the-green-bond-roadmap/

- ICMA. (2021). Green Bond Principles: Voluntary Process Guidelines for Issuing Green Bonds. https://www.icmagroup.org/sustainable-finance/the-principles-guidelines-and-handbooks/green-bond-principles-gbp/

- Kreibiehl, S., T. Yong Jung, S. Battiston, P. E. Carvajal, C. Clapp, D. Dasgupta, N. Dube, R. Jachnik, K. Morita, N. Samargandi, M. Williams. (2022). Investment and finance. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. doi: 10.1017/9781009157926.017

- Mackenzie, C & Ascui, F. (2009). Investor Leadership on Climate Change: An analysis of the investment community’s role on climate change, and snapshot of recent investor activity. United Nations Global Compact. Available here.

- New, M., D. Reckien, D. Viner, C. Adler, S.-M. Cheong, C. Conde, A. Constable, E. Coughlan de Perez, A. Lammel, R. Mechler, B. Orlove, and W. Solecki. (2022). Decision-Making Options for Managing Risk. In: Climate Change 2022:Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 2539–2654, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.026.

- Republic of Kenya The National Treasury and Planning. (n.d.) Kenya Sovereign Green Bond Framework. https://www.fsdafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Kenya-Sovereign-Green-Bond-Framework.pdf

- Rosembuj, F. and Bottio, S. (2016). Mobilising private climate finance – green bonds and beyond. EMCompass,no. 25; International Finance Corporation, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/30351

- Tuhkanen, H. (2020). Green Bonds: A Mechanism for Bridging the Adaptation Gap? SEI Working Paper, Stockholm Environment Institute. Available at: The Stockholm Environment Institute.

- Weber, O., & Saravade, V. (2019). Green bonds: current development and their future. In Green bonds: current development and their future: Weber, Olaf| uSaravade, Vasundhara. Waterloo, Ontario: Centre for International Governance Innovation. https://www.zbw.eu/econis-archiv/bitstream/11159/3354/1/Paper%20no.210_0.pdf

- World Bank. (2015). What are green bonds? http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/400251468187810398/What-are-green-bonds

Further resources

- Financing from the Ground Up – Experiences in Adaptation Finance from Southeast Asia

- Climate finance: is it making a difference? A review of the effectiveness of multilateral climate funds

- Guidebook: Mobilising private sector finance for climate change adaptation

- Financing transboundary water investments – from public good to shared interest

- The Roles of the Private Sector in Climate Change Adaptation – an Introduction

- An introduction to Financing Urban Adaptation

- Introduction to Sustainable Finance: UN CC:e-Learn course

- A framework for mobilizing private finance and tracking the delivery of adaptation benefits

- Bottom-Up Innovation for Adaptation Financing – New Approaches for Financing Adaptation Challenges Developed Through Practitioner Labs

- Engaging the private sector in financing adaptation to climate change: Learning from practice

(0) Comments

There is no content