Cambodia

Introduction

This article was created as part of work to support SIDA staff working on climate change in Cambodia. This work was carried out with Sida’s Environmental Economics Helpdesk and as well as being stand-alone has also been integrated into a broader Environment and Climate Change Policy Brief for the Sida embassy in Cambodia. This article was written by Ben Smith and Chanthy Sam (SEI Oxford and SEI Bangkok), with input from colleagues in SEI Bangkok. A report from the 1st Cambodian National Climate Change Forum in Oct 2009 gives further details of plans for coordinating climate change in Cambodia.

Current Climate and Hazards

Map of Cambodia

Like other countries in SE Asia, the climate of Cambodia is dominated by the monsoon system, which creates two main seasons in the country, with rain from May-November and a dry season from November-May. Annual rainfall varies within the country, with coastal areas receiving up to 5000mm of rain. Rainfall declines in the central plains but is strongly influenced by topography and increases in the upland areas. Maximum temperatures reach 38C and minimums rarely dip below 10C. Mean monthly temperatures vary between 22C and 28C[1].

The annual flooding of the Mekong River and Tonle Sap Lake is essential for agriculture, but the unpredictability of the flooding can damage infrastructure, agriculture and livelihoods; for example severe floods from 2000-2002 affected 3.4m people and destroyed 7086 houses[2]. Cambodia also suffers from droughts, often in the same year as floods. In both cases the major physical cause of these disasters is the unpredictability of rainfall and dry-spells, both inter-annually and within seasons, and high levels of rural poverty and dependence on agriculture and fisheries as the basis for livelihoods exacerbates the impact of these events. Community surveys carried out in preparation of the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) note that while coping strategies exist for these hazards they are limited in their effectiveness and often reinforce poverty and increase vulnerability to the next hazard. Cambodia also suffers from climate-sensitive diseases such as Malaria and Dengue Fever[3]. Windstorms, which happen two or three times a year, are a hazard in rural areas and often damage houses[4].

The factors that govern the strength and timing of the monsoon are complex, with relationships to several regional climatic phenomena such as the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and snow cover in Eurasia. The relationships are not entirely understood, making the predictability of the monsoon a major issue throughout the region. There is a broad pattern, however, that El Nino brings drier conditions and La Nina brings wetter conditions.

Trends

Due to conflict there are very few long-term observations of climate, making it difficult to determine significant and reliable trends in climate, or potential signals of climate change. Work from UNDP and the University of Oxford uses a variety of methods to fill in as proxies for missing observations and states that there has been an increase in temperature of 0.8C since 1960, but no significant change in annual rainfall[5].

Projections of Climate Change

The lack of observations is also a constraint on the development of credible projections of climate change at the country-level; for example while there are downscaled projections from multiple models available for neighboring countries such as Thailand, none currently exist for Cambodia.

The IPCC provides a summary of projections from 21 climate models for SE Asia as a region, which states that temperatures will increase in the range of 1.5-3.7C for the period 2081-2100 and that most models agree that rainfall will increase, ranging from a -2% decrease to a +15% increase[6]. The UNDP/Oxford analysis is similar. Along with the increase in average temperatures it is expected that the number of extremely hot days and nights will increase and the number of cold days and nights will decrease. It also appears that there will be an increase in the intensity of precipitation.

Sea-level rise will be an important issue for Cambodia both because of direct effects on Cambodia’s coastline, and possible indirect effects on Cambodia from sea-level rise in the rest of the region. The IPCC in 2007 assessed that sea-level was likely to rise by 0.18-0.56cm by 2100; however several recent reports conclude that this was an optimistic range and that a rise of around 1m is much more likely (e.g. Rahmstorf 2007[7], New Scientist 2009[8]). Local effects such as land subsidence may amplify the global effect.

It is important to note that the local response to climate change is likely to be significantly different to these general projections. In Cambodia this is likely to be particularly the case in upland areas and around the Tonle Sap Lake. In addition to these local responses, the effect of climate change on the monsoon system is unclear due to the many and complex interactions which affect it. This has the effect of adding uncertainty to projections of change in precipitation in Cambodia and means it is crucially important to use projections from a range of climate models in planning adaptation to climate change, in order to gain an understanding of the range of possible climate responses. The lack of more detailed climate projections for Cambodia is a clear gap that needs to be addressed, however, as discussed below, should not constrain action on adaptation.

Impacts

Uncertainty over changes in climate means that it is impossible to be certain about the precise nature of the impacts of climate change in Cambodia. Very few impacts of climate change will be completely novel, rather it is likely to compound and multiply current problems and stresses[9]. The starting point therefore is existing problems and hazards that may be amplified by climate change.

Even in the case of sea-level rise we see that the salinization of surface and groundwater resources is already identified as a problem in all of Cambodia’s coastal provinces[10] and one effect of climate change will be to amplify this existing problem. In addition to salinization, sea-level rise is expected to increase coastal erosion and may lead to the inundation of economically important coastal infrastructure such as ports and coastal resorts. Higher sea level is likely to increase flooding from storms and storm surges[11].

With 800 deaths/year Cambodia already has the highest Malaria fatality rate in the region and, according to a 2002 government report, the true figure could be 5-10 times that[12]. Given the relationship between Malaria transmission and warm and wet conditions it is expected that the incidence of Malaria will increase due to climate change. A Ministry of Health report in 2002 estimated that cases of malaria could increase by up to 16%. The same is true of other vector-borne diseases such as Dengue fever; an unprecedented large outbreak of Dengue fever in 2007 may be a warning of the outbreaks that can be expected in the future[13]. An increase in vector-borne diseases is likely to predominantly affect poor rural communities who are currently most vulnerable to Malaria as they lack access to healthcare facilities. It is unclear exactly what effect climate change will have on floods and droughts, due in large part to uncertainty over changes to the monsoon regime. It is clear however that the hydrological regime will change, in particular in the case of the Mekong, which receives much of its flow from glacier melt upstream which will become increasingly less reliable. This may make the annual flooding of the Mekong River and Tonle Sap Lake less predictable, and at present it is the unpredictability of floods and droughts that causes the greatest problems, rather than the severity of the events themselves. One study by Hoanh et al in 2004 suggested that peak monthly flow in the Mekong could increase by as much as 41% for by 2071-2099, increasing the risk of wet season flooding, but that minimum monthly flow could decline by 17-24%[14]

Data from the last five years indicates that rice production loss in Cambodia was mainly due to the occurrence of flooding (more than 70% loss) and followed by drought (about 20% loss) and others such as pest and diseases (10% loss). As well as losses from extreme events, climate change may also decrease yields of staple crops such as rice by the end of the century[15]. In addition, although rainfall regionally is expected to increase, increasing temperatures will increase evapo-transpiration and reduce soil water availability, increasing the severity of droughts when they do occur. An increase in the number of flash floods can be expected due to the likely increase in intensity of rainfall. Significant uncertainty over the response of the monsoon system to climate change means that larger impacts should not be ruled out.

The National Communication states that the area of wet forest in Cambodia would decrease while moist forest would increase and dry forest would remain the same, although this depends on exactly how rainfall changes. Forest productivity and biodiversity might also change. High rates of deforestation will accelerate the loss of forest biodiversity, reduce forest productivity and reduce the resilience of the forest ecosystem to climate change[16]

The tourism sector may be affected to some extent by climate change, but this is more likely to be through complex indirect effects – such as aviation taxes in Europe as a response to mitigate climate change – than direct physical effects, except in the case of the possible loss of tourist infrastructure in the coastal zone. Given the many other societal factors, which influence tourist flows, climate change is likely to play only a minor role in determining tourist flows to Cambodia.

As with current hazards, it is marginalized and vulnerable communities, lacking the capacity to deal with climatic shocks, who are likely to be most affected by climate change[17]. Communities who find it hard, or are unable, to cope with current climatic hazards will find it difficult to respond to the additional stresses that climate change may bring. The reliance on agricultural activities as the basis for many rural livelihoods means that they are directly affected by climatic conditions, and therefore sensitive to any changes in climatic conditions, which increases their vulnerability to climate change.

A recent ADB study for South-East Asia (Philippines, Thailand, Viet Nam and Indonesia) suggests that the cost of climate change could be 6.7% of GDP by 2100[18]. No figure is available for Cambodia, but the ADB work should be viewed as indicating that the cost of climate change for Cambodia without adaptation could be significant.

Adaptation

Uncertainty over the exact impacts of climate change should not be taken to mean that there is nothing that we can do to start adapting to climate change. It is clear that adaptation must start from addressing existing problems, both because if we cannot deal with current climate related problems then we are unlikely to be able to deal with the amplifying effect of climate change, and in order to support current national development priorities[19]. One way of doing this is to create strong links between adaptation and disaster risk reduction activities in Cambodia to create both immediate benefits and also longer-term benefits in preparing for climate change (see Box 1)

In many ways adaptation is less to do with technical fixes such as dams, sea-walls and improved crop varieties, and much more about creating the institutional capacity to be able to monitor, assess, plan and implement policies and strategies which will build adaptive capacity across the different sectors of society. Technical solutions will be needed to certain problems, but without strong and effective institutions then adaptation will remain a set of disjointed projects rather than a joined-up strategy which reduces the negative effects of climate change.

In this respect it is important to explore both national capacity and also regional capacity, particularly as many of the issues raised by climate change are likely to require regional coordination and response. In particular management of the water of the Mekong River will require strong regional cooperation and sharing of information, for example to prepare downstream countries for approaching floods. Existing institutions such as the Mekong River Commission and programmes such as the EU-funded Partnerships for Disaster Reduction Southeast Asia have the potential to take on part of the effort needed for climate change adaptation. Emerging initiatives such as the Regional Climate Adaptation Knowledge Network for Asia seek to explicitly build regional capacity and knowledge-sharing on adaptation in the region.

In Cambodia, the NAPA highlighted the following barriers related to capacity for adaptation that will need to be addressed:

- limited financial resources or funding for climate change related activities, especially in the health and agriculture sectors

- few climate change studies and little experience within the country;

- lack of climate change research and/or training institutions in the country;

- lack of data availability and reliability and, in particular, absence of a formal mechanism for information sharing;

- limited cooperation and coordination among institutional agencies related to research or studies on climate change and climate variability;

- relatively low technical capacity of local staff;

- relatively low government salary and limited incentives from the climate change project;

- non-comprehensive national climate change policies and/or strategy;

- lack of qualified national experts in the country;

- limited public awareness and education on climate change; and

- limited technical, financial and institutional resources for adaptation

Much of this list can be distilled into issues of a lack of awareness of climate change (and thus lack of qualified staff and resources), problems of information availability and sharing and limited practical experience in climate change. However, with some training, experience in rural development and across a range of natural resource sectors could be transformed into capacity to respond to climate change.

Sea-level rise is a long-term problem but planning needs to start now to provide the best chance of minimizing its negative effects. This long-term planning cannot be separated from current coastal zone activities. Current stresses need to be reduced in order to increase the resilience of the coastal zone, for example combating the destruction of protective mangrove forests, and coastal development must be managed in such a way that it minimizes development in areas likely to be impacted by sea-level rise. Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) is an approach being used in many countries to address the differing needs and desires of the many groups with interests in the coastal zone [20]. The idea is to harmonize different policies and ensure that the different interest groups are working towards common goals for the coastal zone. ICZM has the benefit of addressing current coastal issues while also taking a long-term approach in order to deal with issues such as sea-level rise.

There is a clear need for an improved observational network on meteorology and hydrology to allow for both improved early warning systems and better monitoring of the way in which climate changing in order to inform adaptation decisions. The digitisation of Department of Meteorology records 1980 would help to explore current climatic variability and any trends there have been in climate[21]. The digitisation of these records could also form the baseline for developing sub-national scenarios of climate change to explore projections from a range of different climate models[22]. Without being a ‘prediction’ of change, this would provide additional information with which to make adaptation decisions.

There are no national estimates of the cost of adaptation so at present all we can say is that the cost is likely to be significant, but less than the cost of full climate change impacts and no adaptation. This is an area where further research is needed.

Mitigation

The reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in Cambodia should not by itself be a priority. Emissions of greenhouse gasses are low, and in the international context it is expected that countries like Cambodia would be allowed to increase their per capita emissions under any deal to agree the successor to the Kyoto Protocol in Copenhagen in December 2009. Proposals for targets which are based on per capita emissions rather than total emissions suggest around 2 tonnes/capita/year (e.g. Stern 2008[23]), whereas at present Cambodia emits 0.29t/capita[24].

It is important to note the emphasis placed by the government of Cambodia on the 2005 discovery of proven and commercially viable reserves of off-shore oil and gas[25]. Proven reserves are estimated at 700m barrels of oil and 5 trillion m3 of natural gas and will heavily alter Cambodia’s energy pathway and emissions of greenhouse gasses. In developing these fuels it is important that technical support is provided to ensure that the environmental impact of their exploitation is minimized. Proceeds from these fuels could also be used to contribute to sustainable development by driving a low carbon rural electrification programme using small-scale renewable energy sources.

The protection of carbon sinks, for example through mechanisms such as REDD (Reducing Emissions from avoided Deforestation and Degradation), which look to protect forests while also providing supporting local livelihoods, have the potential to keep emissions low and also support rural poverty reduction. Equally, low-carbon rural development, for example through the spread of solar-powered cookers or more efficient wood-burning stoves, could also help to minimize emissions and improve rural livelihoods. This is also more likely to bring energy and electricity to rural areas and help to alleviate poverty than large centralized oil and gas projects, which will better serve well connected urban areas.

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and REDD mechanism offer ways of attracting investment and supporting livelihoods while at the same time reducing emissions. Several organisations are exploring the potential for REDD in Cambodia, for example Community Forest International and the Agénce Française de Developpement have a REDD pilot project in Oddar Meanchey with potential savings of 306,000tCO2e. These pilot projects are particularly important as REDD is relatively untested in the field, and the mechanism for delivering emissions reductions and also benefits to local livelihoods will need to be refined before being widely adopted. There are comparatively few CDM projects in Cambodia, partly due to the complicated process of gaining CDM accreditation with the result that several companies, in particular those with small community emissions reductions projects, are turning to the Voluntary Carbon Market instead as a way of reducing emissions[26]. A table of current CDM projects in Cambodia can be found in Annex 1. The extent to which CDM, VCM and REDD projects take off in Cambodia is likely to largely depend on the details of the Copenhagen agreement.

Linking different priorities

In the National Strategic Development Plan 2006-2010 (NSDP), the overarching strategic framework which sets out Cambodia’s plans for development, the government emphasized the desire for greater control over external development assistance to ensure that donor activities were in-line with national priorities and objectives as set out in the NSDP[27]. It is thus important to examine match between the priorities set out in the NSDP, the actions prioritized in the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) and the priorities for SIDA in Cambodia. The current NSDP is being revised into an NSDP for 2009-2013 and it is expected that climate change will be given high priority in the new plan

In the NSDP the government sets out a rectangular strategy to achieve economic growth, poverty reduction and the achievement of the Cambodia Millennium Development Goals (CMDGs)[28]. Climate change is not stressed as a priority, although it is mentioned in sections 2.31 and 4.49. It will be interesting to see to what extent climate change is integrated into the new 2009-2013 NSDP however, even if not explicitly mentioned, many of the priority areas such as rural development, agricultural development, development of the energy sector and the management of water resources are intrinsically linked to climate change and will need to incorporate it in their plans. The key is to ensure that the activities which are undertaken as part of Cambodia’s national development process contribute to building adaptive capacity for climate change and also take climate change into account in such a way that it doesn’t prevent those development goals being met.

The NAPA was formulated with the specific aim to support the priorities of the rectangular strategy and NSDP. The priority sectors for adaptation outlined in the NAPA are Water Resources and Agriculture, Forestry, Health and the Coastal zone, all of which are in-line with the goals set out in the NDSP, however in order to fully support these, the actions outlined in the NAPA would need to be integrated into different sector strategies. The NAPA itself identified several barriers to its implementation including inadequate financial, technical and institutional resources in national and local government regarding climate change, a lack of awareness of climate change as an issue and the lack of integration of climate change into national development plans.

SIDA’s emphasis on rural development as a key part of its assistance strategy fits well with both the NAPA and NSDP priorities. In addition the focus on democracy and human rights supports many of the objectives of the NSDP, including the desire to further decentralize rural development. The priorities for adaptation outlined later in the document fit clearly within both the national development goals and SIDA priority sectors.

Institutional Context

Cambodia ratified the UNFCCC in 1995 and acceded to the Kyoto protocol in July 2002. Under its obligations to the Convention it submitted its first National Communication in 2002 and started the process for the 2nd National Communication in 2007[29]. A National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) was submitted in 2006, building on a history of projects to address climate hazards in Cambodia (NAPA 2006). So far there has been little implementation of the NAPA projects[30] or specific integration of climate change into national planning processes.

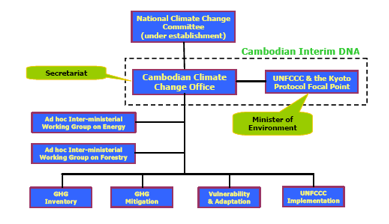

Within government the following diagram explains the main structure for climate change and reporting to the UNFCCC. The Ministry of Environment established the Cambodian Climate Change Office (CCCO) in 2003 and the National Climate Change Committee (NCCC) in 2006. The NCCC comprises senior policy-makers from 19 ministries and serves as a policy-making body that coordinates the development and implementation of policies, plans, and measures to address climate change issues within Cambodia[31]. The NCCC is set as the focal point for all engagement on climate change within the Government of Cambodia .The CCCO works closely with all relevant government agencies, NGOs, private sector, local communities, donors, and IOs to coordinate and implement national climate change policies, greenhouse gas mitigation and inventory, and climate change adaptation activities[32][33]. The Department of Meteorology (DOM) in the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology is also an important actor.

Cambodian structure for reporting to the UNFCCC

The CCCO appears to be well positioned with good links across government and to the private sector and functions fairly well. There is however a clear need for better coordination between the different actors working on climate change in Cambodia such as the government, donors and NGOs. A more active coordination role by the CCCO would be of great benefit[34]. A particular coordination between the well established disaster risk management (DRM) community in Cambodia and the developing climate change adaptation community would be of benefit to both groups (see box on Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction). The relevant coordinating body for DRM in Cambodia is the National Committee on Disaster Management (NCDM), which coordinates both emergency response and building resilience to disasters. Two other major disaster networks are the UN Disaster Management Team and the Humanitarian Accountability Network, which includes international and national NGOs working on disaster management (ADPC). The Strategic National Action Plan on disaster risk management (SNAP) has tried to look for synergies with the NAPA, however, climate change has not yet been mainstreamed in disaster management (ADPC). The NCDM chairs a regular forum that brings together the different actors working on disaster management for coordination and exchange[35]. Involving those working on climate change adaptation in these forums might be a good initial step towards coordination.

Other donors

Donors are becoming increasingly active in the field of climate change in Cambodia, but many activities are in the planning phase rather than currently operational. Cambodia is one of 10 countries in the World Bank Pilot Programme for Climate Resilience and is expected to receive $50m for climate change adaptation, and in particular to build on the NAPA and support the integration of climate change into national development and sectoral plans. The PPCR is working through the Ministry of Economy and Finance rather than the NCCC, designated by the government as focal point[36] Cambodia is also a pilot country in the EC’s Global Climate Change Alliance, the major focus of which will be to support capacity development and aid coordination on climate change. Two projects are planned to follow-up activities suggested in the NAPA; a UNEP project on adaptation and vulnerability in the coastal zone and a UNDP project on climate resilient water management and agricultural practice in rural Cambodia. A larger table of activities is given in Annex 2.

At the regional level there are several initiatives getting started which aim at enhancing regional capacity to adapt to climate change. The SENSA funded Regional Knowledge Platform for Climate Change Adaptation in SE Asia will launch in October, an Asia part of the UNEP led Global Climate Adaptation Network is in planning phase, and the Mekong River Commission launched a Climate Change Adaptation Initiative in August. At this early stage it is unclear exactly what the scope of these initiatives will be, the focus of each and what the relationship between them is.

With the increasing number of activities related to climate change in Cambodia is important that the NCCC and CCCO play a strong coordination role so that the different activities are complementary and truly act to build capacity on climate change, rather than projects occurring in a disjointed manner. An effective mechanism for sharing information and experiences between the government, donors and NGOs in order to promote enhance knowledge and capacity on climate change is important if the potential benefit from increased donor activity in Cambodia is to be realized.

References

- ↑ RGC 2006 Cambodia National Adaptation Programme of Action

- ↑ Danida 2008 Climate Change screening of Danish development cooperation with Cambodia.

- ↑ WHO Climate Change Country Profile Cambodia. http://www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/EF203FE3-0C6F-475F-B9C7-5C67364910E3/0/CAM2.pdf

- ↑ Ministry of Environment, (March 2005): Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Hazards and to Climate Change: A Survey of Rural Cambodian Households. Phnom Penh, Cambodia

- ↑ McSweeney, C., New, M. and Lizcano, G. 2008 UNDP Climate Change Country Profiles: Cambodia

- ↑ Christensen, J.H. et al. (2007): Regional Climate Projections. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- ↑ Rahmstorf, S. 2007 A semi-empirical approach to projecting future sea-level rise. Science 315: 368-370.

- ↑ Ananthaswamy, A. Sea-level rise: I’ts worse than we thought.. New Scientist 2715, Jul 01 2009.

- ↑ Adger, N. et al. 2003 Adaptation to Climate Change in the Developing World. Progress in Development Studies 3: 179-195

- ↑ RGC 2006 Cambodia National Adaptation Programme of Action

- ↑ Danida 2008 Climate Change screening of Danish development cooperation with Cambodia.

- ↑ RGC 2006 Cambodia National Adaptation Programme of Action

- ↑ WHO Climate Change Country Profile Cambodia. http://www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/EF203FE3-0C6F-475F-B9C7-5C67364910E3/0/CAM2.pdf

- ↑ Cruz, R.V. et al 2007 Asia. In Climate Change 2007 Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. IPCC 4th Assessment report.

- ↑ ADB 2009 The Economics of Climate Change in SE Asia: A Regional review.

- ↑ RGC 2002 Cambodia’s Initial national Communication under the UNFCCC.

- ↑ In Cambodia, about 84% of the population is living in rural areas, many of which live in risk-prone areas and lack the resources to adapt (RGC, 2001)

- ↑ ADB 2009 The Economics of Climate Change in SE Asia: A Regional review. Figures should be taken as indicative due to the large physical and socio-economic uncertainties involved.

- ↑ In many cases good development activities, such as improved sanitation and healthcare coverage to combat Malaria, will have both immediate benefits and also reduce the impact of climate change.

- ↑ UK Department of Food, Environment and Rural Affairs 2009 Integrated Cosatal Zone Management. http://www.defra.gov.uk/marine/environment/iczm.htm

- ↑ Danida 2008 Climate Change screening of Danish development cooperation with Cambodia.

- ↑ These can be made at the scale of individual weather stations, and have been carried out for neighbouring countries such as Thailand and Vietnam.

- ↑ Stern 2008 Key elements of a global deal on climate change. LSE

- ↑ IEA 2009 Energy indicators for 2006.

- ↑ RGC 2006 National Strategic Development Plan 2006-2010

- ↑ Danida 2008 Climate Change screening of Danish development cooperation with Cambodia.

- ↑ RGC 2006 National Strategic Development Plan 2006-2010

- ↑ The CMDGs include all of the UN Millennium Development Goals, and also a goal related to reducing casualties from unexploded ordnance.

- ↑ Cambodian Climate Change Office 2009

- ↑ UNEP and the GEF have agreed to fund a project on coastal zone restoration but this is not yet operational.

- ↑ Danida 2008 Climate Change screening of Danish development cooperation with Cambodia.

- ↑ It is unclear from this review exactly what the relationship and division of responsibility between the NCCC and the CCCO will be.

- ↑ Cambodian Climate Change Office 2009: http://www.camclimate.org.kh/1AboutUs/MOEDecision.htm

- ↑ Danida 2008 Climate Change screening of Danish development cooperation with Cambodia.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTCC/Resources/CambodiaAcceptanceTemplate_F.pdf

(0) Comments

There is no content