Climate-resilient development for Somalia

Introduction

Somalia is among a group of countries designated as ‘fragile’ by the World Bank; this fragility has created high vulnerability to climate extremes and change. Despite this, Somalia receives little climate finance compared to other countries. There is a need to better understand what barriers and enablers exist in-country to address the adverse impacts of today’s climate hazards and prepare for climate change.

So far, bilateral and multilateral funding has been fundamental to financing climate-related activities in Somalia, but there are missed opportunities in acquiring funding and effective use of the scarce finance. In addition, adaptation priorities identified in national climate and sectoral policies in Somalia do not yet adequately address the range of climate risks to the country’s economic and social development.

This report outlines ways that policymakers in Somalia can increase access to climate finance and better integrate adaptation, mitigation and disaster risk management in socioeconomic development. It draws on desk-based research, an independent analysis of existing climate projection datasets from authors with expertise in climate data analysis, a climate risk assessment, and extensive stakeholder consultations with key actors from the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) and bilateral and multilateral financial providers.

This article is an abridged version of the original text, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, full references, or to quote text.

Government development priorities

The FGS has laid out the vision to transition the country from dealing with protracted humanitarian crises into a country with a vibrant and diverse economy. The Somalia National Development Plan 2020 to 2024 (the Ninth National Development Plan; NDP9) uses this vision to define a future based on poverty reduction, inclusive growth and development.

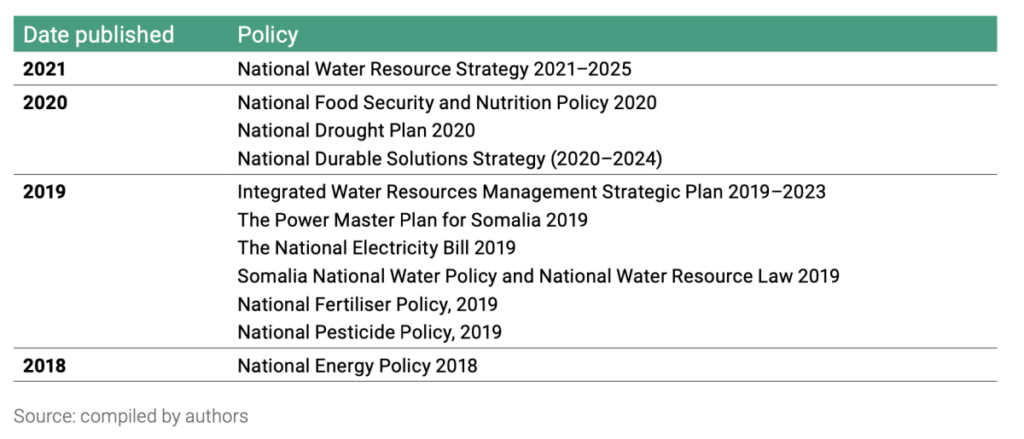

The objectives of the NDP9 are anchored on four pillars, namely: (1) inclusive politics, (2) security and rule of law, (3) economic development and (4) social development. The objectives and goals articulated in NDP9 are being used in conjunction with different sector policies (see table below) to move the country beyond the current status quo where local livelihoods are highly vulnerable to climate, conflict and financial shocks and stresses to a more inclusive, resilient and diversified economy.

Despite Somalia being prone to droughts and heavy rainfall events, climate-related issues are currently addressed in an ad-hoc manner and require better embedding within socio-economic development and land-use planning. Adaptation of human systems and protection of Somalia’s ecosystems to facilitate their adaptation are processes that need to be embedded within Somalia’s development so that it is climate resilient, equitable and just, keeping in line with the NDP9’s priority pillars of inclusive and accountable politics and improved security and the rule of law.

Climate risks to Somalia’s development

The report focuses on climate change risks to five cross-pillar socio-economic sectors mentioned as priorities in the NDP9 under ‘Pillar 3: Economic development’ and ‘Pillar 4: Social development’: (1) water, (2) energy, (3) urbanisation, (4) agriculture and (5) livestock. Here we present an abridged version of the report’s findings. Please read the full report for more details.

Short-term risks: 2021-2040

Water sector risks:

- Water risks for Somalia over the short to long term will be heavily mediated by changes in demand related to urbanisation and economic diversification; land-use planning and change; conservation plans and measures; and the planning, construction and maintenance of infrastructure for irrigation, livestock watering points and urban use.

- Climate-driven shifts in temperature and precipitation means and extremes will compound changes in water demand and use. Despite uncertainty in short-term precipitation, the increases in maximum daytime temperature and minimum night-time temperature will lead to higher evaporation and reduced aquifer recharge in some groundwater systems.

Energy sector risks:

- There is currently a high dependency on charcoal for cooking in rural and urban areas, and it is a significant source of income for rural households. However, charcoal production is also leading to deforestation.

- Planning, construction and maintenance of energy infrastructure will have to be cognisant of significant increases in energy demand and of higher temperatures and greater precipitation extremes.

Urbanisation risk:

- Urban expansion through 2030 could be significant due to influxes of Internally Displaced People fleeing drought and conflict areas to stay in towns and cities.

- People living in substandard housing are particularly vulnerable to heatwaves – such as shanty structures that lack cooling and ventilation. Such housing is also more likely to be damaged or destroyed in extreme rainfall events.

Agricultural risks:

- Maize yields in Somalia could decline by 20% to 50% due to hotter temperatures, which presents challenges for farmers and crop production objectives articulated in the NDP9. Sorghum is more resilient to warmer temperatures and extended dry periods than maize crops; however, locust plague outbreaks are also likely to increase in frequency, given their linkages to heavy rainfall and the possibility of an increase in the intensity of rainfall events.

- Water availability will play a vital role in agricultural productivity.

Livestock risks:

- Heat stress in livestock presents a significant risk to Somalia’s livestock sector over the short to long term. Heat stress risks can also generate cascading gendered nutrition and economic risks amongst pastoralists and agro-pastoralists.

- Dryland forage yields could also reduce due to the potential increase in extreme precipitation events, more dry spells and shifts in the onset and duration of the Gu and Deyr rainy seasons, and higher temperatures in all seasons.

Medium-term risks: 2041-2060

Water sector risks:

- Higher temperatures and increasing frequency, duration and intensity of extreme heat events, coupled with more and longer periods of consecutive dry days over the medium term, could further impact some aquifers’ recharge and yields, and the concentration of minerals and pollutants in water supplies.

- Domestic water demand will grow, particularly in urban areas. Domestic demands in southern Somalia could grow from approximately 51.2 hm3 in 2005 to 235.7 hm3 in 2055 if urbanisation rates reach 60%.

Energy sector risks:

- The Jubba River basin is highly exposed to increasing evaporative losses, hotter temperatures, and more fluctuations in streamflow over the medium and long terms – affecting hydro-power along the river.

- Somalia has significant solar and wind potential. However, elevated temperatures, sand scouring due to soil erosion and lack of water present challenges to wind and solar generation, as well as to transmission lines.

Urbanisation risks:

- Urban heat island effects will magnify the impacts of heatwaves, particularly for urban areas in the north and the interior southern and southern-central coast regions. By the medium term, the number of days per year exceeding 40°C could range from 40 to 100+ days, depending on the region.

Agricultural risks:

- The January–February season is likely to become wetter over the medium term. This may lead to greater harvest losses among cereal crops, with wetter and warmer conditions leading to crop fungal infections and rot pre- or post-harvest, locust outbreaks or other crop pest issues

- Heat stress in crops leading to decreased yields and crop losses is very likely in the medium term, depending on the temperature thresholds of specific crops.

Livestock risks:

- The frequency of heat stress days that could endanger livestock – particularly sheep and goats – is projected to increase significantly in Somalia over the medium term.

Climate adaptation priorities

Government disaster risk and adaptation priorities

Somalia’s environmental and climate change policies generally aim to transition to climate-resilient development by reducing vulnerabilities to climate hazards and climate-related disasters, and increasing adaptation capacity. Sectors prioritised under almost all policies are agriculture, water resources, forestry and the marine environment. Disaster preparedness and response to extreme weather/climate events have been identified as additional priorities.

However, not all climate risk management priorities of NDP9 have been adequately addressed through existing climate policies. The report also highlights gaps within climate policies.

Partner disaster risk and adaptation priorities

A non-exhaustive review of the current priorities of the main humanitarian and development actors working in Somalia suggests that adaptation to climate change is not always an explicit priority area of support within their country strategies; however, most development partners are supporting adaptation to climate change through projects and programming directed towards improving food security, protecting livelihoods, strengthening agricultural value chains, supporting economic diversification and strengthening resilience more broadly.

Development partners are increasingly looking at interventions that not only support short-term needs but also enable longer-term adaptation and climate-resilient development by offering opportunities for micro socio-economic and macro socio-economic benefits and peace dividends.

A key issue identified is that humanitarian and development actors have separate coordination mechanisms, and coordination between these two groups remains indirect at best.

Climate risk and resilience in aid interventions

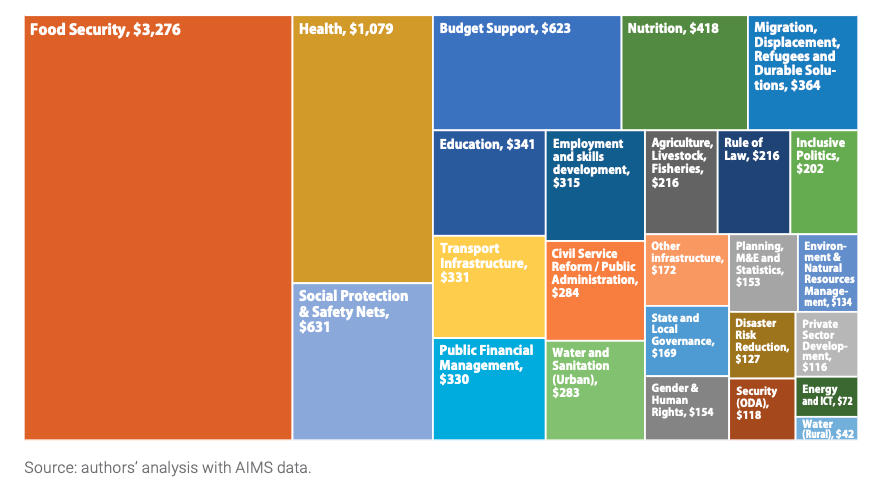

The lack of a shared understanding of climate change risks between the different actors responsible for resilience building, including development, humanitarian, climate and other stakeholders, affects the quantity and quality of interventions aimed at building climate adaptation in Somalia. Presently, most official international finance to address climate impacts is provided through short-term humanitarian relief, while dedicated climate finance to build longer-term climate adaptation is less than 6% of annual needs.

Key findings

Several entry points exist that the Federal Government of Somalia, supported by development, humanitarian and climate adaptation actors, can leverage to increase access to climate finance and begin incorporating adaptation, mitigation and disaster risk management within socio-economic development and transition to climate-resilient development. Such entry points include:

- Strengthening the capacity of the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change (MoECC)

- Improving climate data acquisition under the Somali Water and Land Information Management (SWALIM) system

- Enhancing coordination, collaboration and coherence across development, humanitarian partners and accredited agencies to the vertical climate funds*.

* Note: Vertical funds are development financing mechanisms confined to single development domains with mixed funding sources.

Policy implications

Adaptation priorities identified in national climate and sectoral policies do not yet adequately address the range of climate risks to Somalia’s economic and social development. Climate risks are being addressed in an ad-hoc manner and prioritise immediate and short-term impacts and needs, rather than preparing for future shifts in temperature, extreme weather, rainfall and water supply or preparing for changes to livelihoods, water demand and urbanisation. Understanding and framing adaptation priorities in accordance with Somalia’s development priorities, and presenting a unified vision at federal, state and municipal levels, is fundamental for transitioning to climate-resilient development.

Suggested citation

Gulati, M., Opitz-Stapleton, S., Cao, Y., Quevedo, A. (2023). Climate-resilient development for Somalia. SPARC Report.

Related resources

Related resources

- Accelerating adaptation action in Africa - Insights from African experts

- Synthesis report: Exploring the conflict blind spots in climate adaptation finance

- Climate Finance for Sustaining Peace: Making Climate Finance Work for Conflict-Affected and Fragile Contexts

- https://www.weadapt.org/knowledge-base/adaptation-without-borders/an-african-perspective-on-transboundary-and-cascading-climate-risks

- Climate variability and impact in ASSAR’s East African region

(0) Comments

There is no content