Spekboom Carbon Sequestration and Rehabilitation Project in South Africa

Introduction

Applied good practice principles:

1. Knowledge building

Research into the degradation and restoration of Subtropical Thicket vegetation in the Eastern Cape has provided a rich source of published literature (click on Good Practice Case link below) as well as the subject of a number of MSc’s and PhD’s. Generally these have been focused on ecological issues, i.e. the causes of degradation and strategies for rehabilitation/restoration. The issues of financing restoration, rebuilding natural capital and the generation of carbon credits through the re-establishment of spekboom have featured in a chapter from the book “Restoring Natural Capital: Science, Business, and Practice” published by the Society for Ecological Restoration. South African universities involved in aspects of the research included Rhodes University, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University and the University of Stellenbosch.

2. Community participation and inclusiveness

The project is essentially a top-down project initiated and overseen through various academic and government departments. Community participation operates at two levels. First, public-private partnerships, where private enterprises are responsible for implementation of various aspects of the project, and government are responsible for overseeing the regulation and integration of these aspects. The aspects of the project implemented by private enterprise include the planning and execution of restoration efforts and the registration and marketing of carbon credits.

The second level of community participation is focused on employment and skills development. Community participation occurs through the Working-for-Woodlands Programme which is itself modelled on the Working-for-Water Programme implemented by the Department of Water Affairs. Through the Working-for-Woodlands programme, unemployed people in impoverished local communities gain skills through restoration activities. These workers are selected from previously disadvantaged groups who are the poorest of the poor and must include a quota of women and disabled individuals. These restoration workers develop skills in erecting nurseries, plant propagation, soil and site preparation and tree planting.

3. Political ownership, collaboration and approval

The project is essentially managed by the South African government through the Department of Environment’s Natural Resources Management Programme through various public-private partnerships and fits neatly into the frameworks described in white papers on Sustainable Forestry Development, Conservation and Sustainable Use of South Africa’s Biodiversity and the National Climate Change Response. The government’s motivation for supporting the initiative is three-fold.

In no particular order, the project provides a vehicle for poverty alleviation and skills development. Second, it focuses on restoration of degraded rangelands, and protection and enhancement of biodiversity and natural capital. And third, the project provides a mechanism to build resilience towards future climate change through improved ecosystem function and increased biodiversity. The project also provides tangible evidence of South Africa’s commitment to various international agreements such as the Convention on Combating Desertification, and the Convention of Biodiversity and the Kyoto Protocol.

4. Financial sustainability

Prior to 2004, research into the ecological aspects of spekboom was funded through research grants either administrated by academics through their research programmes or from national sources such as the National Research Foundation (NRF) or its predecessors. In January 2004 the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry launched the Subtropical Thicket Restoration Project which manages the Thicket Restoration Programme. Funding at this stage came solely from government sources. The long-term plan however is to generate verified carbon credits through restoration of spekboom thicket and then generate funds from the sale of these credits to private corporate buyers. These funds from carbon credits will be used to fund further phases of the project. At this point funding has not been generated through the sale of carbon credits. However credits have been validated by certified auditors, and are therefore eligible for sale as ex-ante credits.

5. Achieving co-benefits and balancing trade-off

Economies of scale are important as economic modelling suggests that although returns could be positive, internal rates of return (IRR) are relatively small. Modelling found that the IRR was sensitive to the area planted, the growth rate attained, and the price of carbon credits. Generally, multilateral funding agencies require an IRR of at least 12% before funding a project whereas the default scenario for the Thicket Restoration Project returned an IRR of 9.2%. Within nature reserves or protected areas modifying management actions to promote restoration is relatively easy. To obtain large enough areas though will require the cooperation of private land owners. Commercial farmers usually require their land to be economically active and one trade-off is the fairly immediate return on investment from goat farming versus the delayed return on investment through restoration and carbon credits. Therefore private land-owners or communities with communal land may require alternative income during project establishment phases, as browsing would need to be prevented or restricted depending on the phase of restoration.

6. Building local capacity

The Thicket Restoration Project contributed to building local capacity at two levels. First, aspects of the project were the subject of a number of Master’s and Doctoral degrees at South African Universities. Therefore the project has contributed to the development of internationally competitive biological and environmental skills and knowledge in the next generation of professional scientists and environmentalists in South Africa. The second level of capacity building is the development of skills for some members of the impoverished and often poorly educated rural communities. These skills, though generally fairly rudimentary, include land preparation and planting, and in some cases group leadership skills. For this group, probably of equal value to building their capacity was the value of being in formal employment and the experience and employment reputation thereby gained.

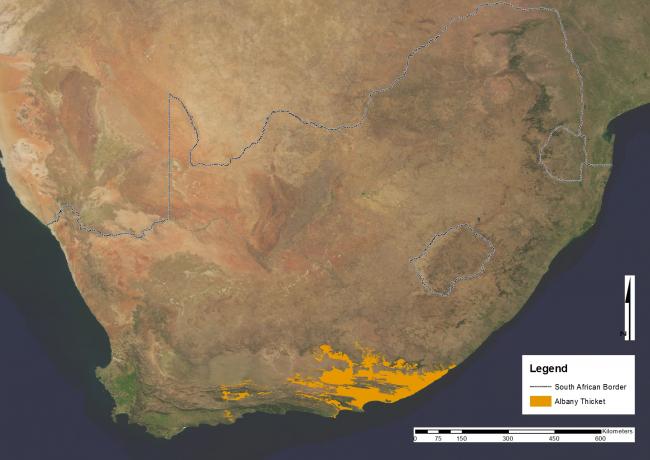

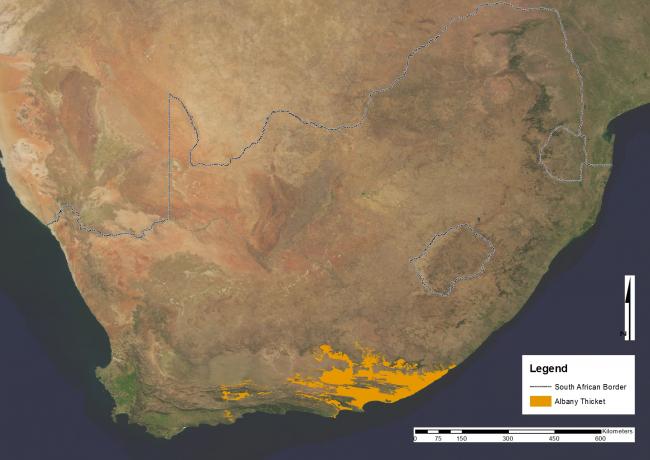

7. Transferable

The project is essentially replicable throughout the Subtropical Thicket Biome, where spekboom was naturally dominant, within the limitations provided by local climate conditions. In 2008, trials were instituted to test the programmes applicability to the entire biome. To replicate the project outside the biome would require identifying species with high carbon-fixation rates and strong soil-carbon sequestration characteristics. As a general assumption, it can be expected that such potential species would most likely have high growth rates to provide the carbon fixation rates required, and either fairly high leaf turnover or strong carbon translocation characteristics moving carbon into roots to maximise soil carbon sequestration.

8. Monitoring and evaluation

The government’s project in Addo Elephant National Park has been validated through the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and the Climate, Community and Biodiversity Alliance (CCBA) standard. The VCS requires all voluntary carbon units (VCUs) to be real, measurable, additional, permanent, independently verified, conservatively estimated, uniquely numbered and transparently listed. To fulfil the obligation of being real, measureable and conservative the project applied methodologies verified by VCS. The methodologies focus on the amount of carbon in the soil, litter and living vegetation pools at the start of the project, monitoring and documenting the change in carbon pools under the project scenario, and estimating project leakage to mention a few criteria.

(0) Comments

There is no content