Supporting climate-resilient urban planning: 10 lessons from cities in southern Africa

The authors of this brief highlight 10 lessons learned from their work to promote and support long-term resilience to the impacts of climate change in growing cities in sub-Saharan Africa. The insights stem from work conducted from 2015 to 2022 through two projects: Future Resilience for African CiTies And Lands (FRACTAL) and its successor, FRACTAL-Plus.

The authors argue that climate services must shift away from a product-driven focus and towards an approach that emphasizes process-driven, decision-making needs and contexts. To this end, they contend that the provision or development of a climate information product should be viewed as just one component of a climate service process, rather than its ultimate goal. The authors suggest that climate services are likely to be more effective and longer lasting when the emphasis is on learning, relationships and networks built through engagement processes.

This article is an abridged version of the original text, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, full references, or to quote text.

10 lessons to support climate-resilient urban planning

We offer these 10 lessons to guide researchers, practitioners and urban stakeholders designing adaptation projects in both the Global South and North on how to address climate resilience and to prioritize key elements to help transform urban planning with the human and financial resources that are available.

1. Facilitate inclusive and empowered collaboration

An empowering foundation for locally led, sustainable urban planning can be provided by using skilled and inclusive facilitation to help diverse stakeholders co-create priorities, goals and knowledge.

Throughout the FRACTAL project, each city held multi-day Learning Labs: transdisciplinary sessions that involved many different interest groups, including city planners, councillors, community representatives, the private sector, civil society, researchers and others. The Learning Labs were designed to identify the most important and urgent common issues that participants faced so as to create a shared understanding of challenges, priorities, agendas and potential solutions.

2. Create formal collaboration mechanisms

Formal institutional mechanisms to link city councils, local universities and the project can ensure that participants have the time and resources to work together.

Formalized institutional processes fostered collaboration between the project, and each local university and council within each city. A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the three institutions enabled seamless sharing of city development priorities (from city officials and practitioners) and climate and social science (from researchers).

This approach created a fertile middle ground where policy and climate science met. It was in this middle ground with the city officials and scientists having clear locus standi in the research that FRACTAL delivered innovations, actions and learning, all necessary for locally grounded and inclusive climate resilient development.

3. Place researchers in city government

Embedded researchers and local champions can identify and create entry points to set the stage for longer-term impact.

The MoUs (described above) enabled the innovative mechanism of six early-career researchers to become embedded within city councils in addition to their own research institutions. The project also made use of local champions: highly engaged and proactive individuals in city council departments, local NGOs, or civil society organizations. People in these roles provided information that enabled the project to 3 be continually reflexive, adaptive and responsive.

By virtue of their placement in local governments, the embedded researchers and local champions developed capacity to undertake collaborative and impactful research on climate-related issues, and to understand how such issues are guided by and feed into urban policy and practice

4. Use creative means to exchange different types of knowledge

A holistic understanding of context can be achieved by stepping out of one’s comfort zone to consider the lived experience of local people alongside scientific inputs.

Making use of a variety of creative activities and multimedia techniques (such as interactive games, role plays, participatory decision exercises, cartoons, and visual models) helped to build trust and create a safe space to contribute and share perspectives. To achieve a holistic understanding of context and burning issues, the FRACTAL project went beyond modelling and climate science, to explore stories, surveys, videos, media analysis, other documentation of lived experiences and the psychology driving decisions.

5. Promote trust

A culture of respect and trust promotes collaboration and can lead to more integrated work across disciplines, government departments and governance levels.

Relationship and network building supported better coherence, coordination and collaboration at the level of technical planning and implementation, but also created a mutual understanding of the challenges faced by technical staff and senior decision-makers. The approaches used sought to avoid uncoordinated and maladaptive responses, and to seek out opportunities for synergies.

6. Examine wider contexts

FRACTAL engagements tackled priority issues from a systems perspective.

A systems perspective allowed participants to consider various scenarios and give them an opportunity to distil assumptions and interrogate models (Jack et al., 2021) that would otherwise appear as a “black box”. Finding innovative ways to co-explore climate risk information, uncertainty, and assumptions in data was key to increasing awareness, understanding and capacity about the potential role of climate information in decision-making. A prime example of this was the role played by climate risk narratives.

7. Help cities learn from one another

Cross-city visits and small grants can help institutions act through increased knowledge exchange, learning, collaboration and innovation.

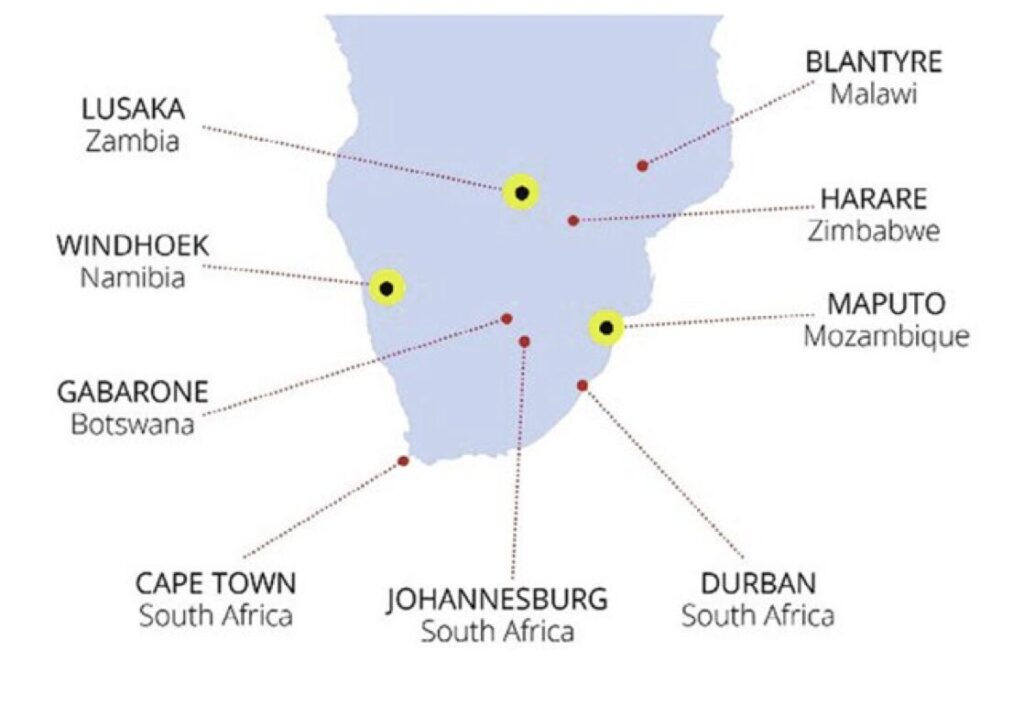

FRACTAL was designed to support city and academic partners to participate in cross-city exchanges that gave them opportunities to share knowledge and experiences about similar challenges they were facing, and potential solutions they were considering. For example, Lusaka and Windhoek delegates visited Maputo. Durban and Gaborone delegates visited Windhoek. An exchange took place between Harare and Lusaka. In addition the FRACTAL Project also funded the exchanges, using its small opportunity grants, a feature that was part of the project’s strategy to allow cities to pursue emerging city-specific topics requiring new research.

8. Boost participants’ confidence

Developing the confidence of participants (both providers and users of climate information) can be as important as responding to their capacity needs.

Activities described above fed into the co-creation of solutions that were owned by local stakeholders in FRACTAL cities. Local agency was strongly supported by responding directly to capacity development and training needs identified during Learning Labs and other engagements, and through city-specific research, and city-to-city visits.

9. Support participants to teach one another

Project participants can learn from one another and can work together in new ways.

The project was deliberately set up to facilitate cross- learning among disciplinary specialties. There were core teams for each city, including internal project- learning clusters on certain issues, such as climate, decision-making and governance. The learning in each team and cluster was iterative, interactive and inter-disciplinary with cluster members bringing together different disciplinary expertise, experiences and skills.

10. Balance political time horizons

Addressing both short- and long-term benefits can help set the stage for decisions that have the potential to withstand political change.

FRACTAL’s work highlighted the importance of implementing solutions that can show both immediate and long-term benefits, sometimes framed as “no-regret” options or those that do not lock planning into a particular pathway, potentially increasing vulnerability in the future.

Outcomes addressing climate-resilient development

The City of Maputo

The city established a Climate Change Department and created a conceptual early warning tool for climate-induced vector- and water-borne diseases. As of this writing, the concept has been upscaled to the national level by the National Institute of Health (INS) and a FRACTAL partner, with the support of the WHO Mozambique country office. INS is now testing an Early Warning, Alert and Response System for climate sensitive diseases.

The City of Windhoek

The city has developed an Integrated Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (ICCSAP). The plan is being tabled for final approval with the Council though changes in the governance structures have delayed this process.

The City of Lusaka

FRACTAL has informed several climate and water related interventions in the city including groundwater protection at two major boreholes, sanitation improvement projects in informal settlements, and waste management strategies and actions. Lusaka City Council used policy briefs co-produced in FRACTAL workshops to inform six Local Area Plans (LAPs) for water security investment, the creation of the Lusaka Water Supply Action and Investment Plan (WSAIP), climate action strategies in the draft Integrated Development Plan (IDP) and implementation of the Lusaka Sanitation Project. The IDP will be the first plan to include a specific strategy for climate change action in Lusaka.

Suggested citation

Bharwani, S., Daron, J., Siame, G., Jones, R. G., McClure, A., Jack, C., Koelle, B., Grobusch L., Zhang, M., Mangena, B., Janes, T., Nchito, W., James, R., Maure, G., Mfune, J., Neal, J., Kaulule, T., Ndhloovu, D., Kaulule, T., and O’Shea, T. (2023) Supporting climate-resilient urban planning: 10 lessons from cities in southern Africa. FRACTAL project: https://www.fractal.org.za/

Related resources

Related resources

- FRACTAL: Future Resilience for African Cities and Lands

- Principles for co-producing climate services: practical insights from FRACTAL

- Learning from climate change perceptions in southern African cities

- Bottom-Up Adaptive Decision-Support for Resilient Urban Water Security: Lusaka Case Study

- Integrating Climate Adaptation: A Toolkit for Urban Planners and Adaptation Practitioners

(0) Comments

There is no content