Djeneba’s story

Introduction

This is Djeneba Djedheou.

Djeneba lives in Dakar, the capital of Senegal. She works as a cook and a nanny for a family in the wealthy part of the city. Djeneba is not untypical of Senegal’s – and Africa’s – growing middle class.

She works long days. And in the evenings, Djeneba takes 3 different, noisy buses to get back to the home she shares with her nieces, sister and auntie. She doesn’t have the time or energy to prepare traditional Senegalese cereals like sorghum or millet: every day, Djeneba eats rice.

Rice is easy and quick to cook. That’s why it makes up around 30% of daily calorific intake for people across Senegal. As the local saying goes: “if you haven’t had rice today, you haven’t eaten”.

The rice that Djeneba eats is imported, mostly from Thailand – some of it from Vietnam. Imported rice is better quality, and the same price, as the small amount of locally produced rice that makes it to markets in Dakar. Almost everyone in Dakar eats imported rice. Every day.

How much of your monthly income do you spend on food? You might struggle to answer that simple question! If you’re anything like the average Swede, you will spend around 12% of your monthly income on food. In the US the average is as low as 7%.

Djeneba knows exactly how much of her monthly income goes on food. It is around 30%, which makes her fairly typical in Senegal. She knows the exact price of rice, each week. Even small changes in the price of rice impact the monthly food intake of families in Senegal.

If the price of rice rises, people eat fewer vegetables and fish, or – if they can – they work more to earn extra cash; or they eat less. “If you hadn’t had rice today, you haven’t eaten”.

That is why the events of 2008 had such a huge impact on Djeneba and her family.

Let’s Zoom out from Senegal for a second and fly quickly to India. It’s 2008 and poor rice harvests are predicted in India. This motivates the government to impose an export ban on rice. The Indian government cannot afford to ignore rice: rice prices are higly political, in India as in Senegal.

India’s export ban triggers a chain reaction: rapid rice price increases, panic buying by middle income countries, a flurry of trade measures across exporting and importing countries: a global rice crisis.

Now let’s zoom back into Senegal: as a low income, heavily import-dependent country, there was little the Senegalese government could do cushion the effect of the global price shock.

The price of rice at the market where Djeneba shops was over 120% higher than normal. What does a family who spend 1/3rd of their monthly income on food do when the price of their staple commodity more than doubles?

Photo credit: Reuters / Normand Bouin

Djeneba took to the streets to protest against her government. Some of her less restrained fellow citizens rioted against the situation, the result of a chain of events that had started half the world away.

Climate change is projected to severely disrupt rice farming in the main exporting countries. If the global market continues to operate as it does today, more frequent and intense droughts are very likely to create new global price shocks.

Meanwhile, as production falters, global rice CONSUMPTION is projected to double by 2050, with much of this new demand driven by urbanisation in Africa.

Climate change increases the risks for food import-dependent countries, making it increasingly difficult for governments like Senegal’s to maintain stable and affordable prices. This threatens the food security of people like Djeneba.

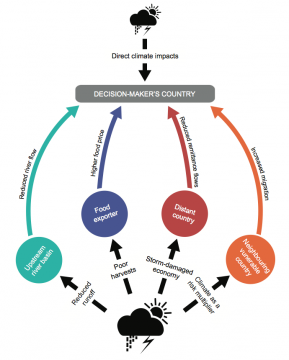

We call this an indirect impact of climate change – people and governments face risks that are the result of climate change somewhere else in the world.

Government decisions will be key in determining how countries adapt to the indirect impacts of climate change, whether they are the result of migration, human health, security, public investments overseas, peacekeeping, transboundary ecosystems or supply chains and trade.

But very few governments are actively planning to adapt to indirect climate change impacts.Many currently lack the right decision making frameworks or the expertise to assess complex, transboundary risks.

So how can a country like Senegal prepare for the indirect impacts of climate change?

We think governments can address the indirect impacts of climate change by applying the framework we have developed within the Adaptation without Borders project at SEI. See the resources available at the bottom of this page.

Our hope is that by learning from other disciplines and actors to better manage trade and supply chain risks in a changing climate, countries like Senegal will develop strategies that keep food prices stable and affordable in future, meaning that people like Djeneba do not have to take to the streets again in protest.

Watch a video of Djeneba’s story, delivered at SEI’s 25th Anniversary Symposium – Stories from a Changing World (@1:01): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mH8yItwxrBg

(0) Comments

There is no content