EcoAdapt: Creating and Sharing New Knowledge Through Joint Learning on Water Governance and Climate Change Adaptation

Introduction

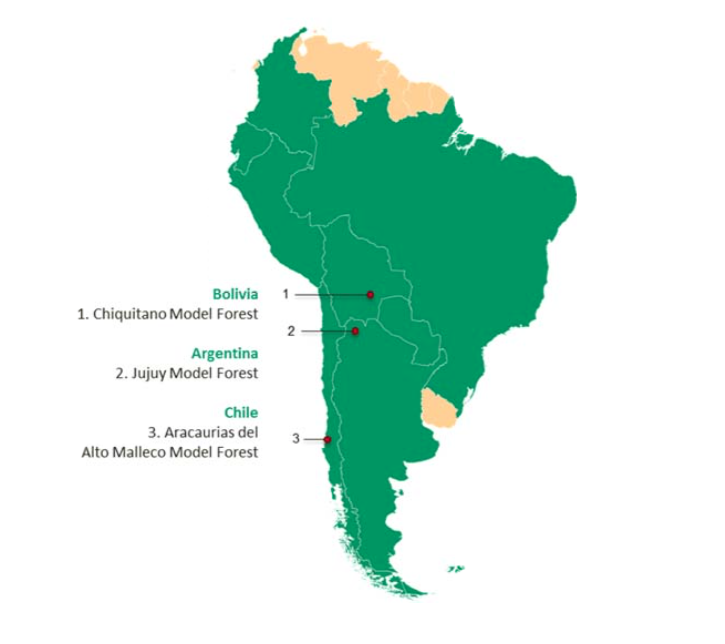

The EcoAdapt Project is a joint undertaking by four research and five civil society organizations from Europe and Latin America, aiming at action-research to enhance local communities’ ownership and implementation of innovative solutions for adaptation of the landscape and people to climate change. Engaging with multi‐stakeholder platforms in three Model Forests in Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, respectively, the project focuses on identification and implementation of measures that would enhance water security for long‐term local development under the influence of climate change. This type of action‐oriented research collaboration is being implemented in a challenging environment of competition between the urgency for improving livelihoods of local people and the need to generate new scientific knowledge.

The underlying principle in the EcoAdapt Project is that all knowledge is valuable, and that both researchers and local actors benefit from adopting a knowledge culture based on joint learning. Researchers learn how to tailor their scientific problem framing, methods, analysis and presentation of results to the context of their counterparts. On the other hand local actors learn about different ways to frame the problem and contribute to possible solutions that scientists can help design.

This IUFRO Occasional Working Paper*provides insights into possible approaches that action‐research projects may follow to promote learning among involved stakeholders. It provides a background on the theories and concepts of joint learning and knowledge development, and proposes a framework to analyze how learning has taken place during the collaborative work developed in the EcoAdapt Project in the phase preceding adaptation planning in three model forests.

*Download the full text from right-hand column or via links under further resources. The main lessons learnt and enabling factors are provided below (abridged).

Lessons Learnt

Based on the work of the EcoAdapt Project in the three model forests, some preliminary insights and lessons learned for strategic development, policy debate and policy‐making can be extracted from the results:

The strategic importance of articulating actors and scales of intervention

Policies and laws which are not rooted in local participation and do not have the support of civil society are typically not effective; conversely, on the ground actions without proper legal and policy backing also has limited impact. It is therefore necessary, and feasible, to shorten the distance between state agencies and civil society, by inviting policy‐makers to participate in dialogues and multi‐actor meetings and platforms.

The same is true when it comes to promoting more articulation among government bodies and civil society organizations in order to make better use of scarce human, institutional and financial resources for addressing environmental, climatic and development issues. Equally important is to enable articulation between geographical scales and different levels of governance.

The strategic and economic value of platforms and agents of change

Cooperation and articulation through institution building is of strategic importance on the road to territorial and community‐based management of environmental and climatic challenges. There are indications that there is good progress in this direction, and there is now (more) clarity on how to get there.

Economically‐speaking, efforts invested in building multi‐actor platforms and creating conditions for actor cooperation and articulation are cost‐effective in the end because they help to establish trust and a common language and vision, to define the roles and functional division of tasks, and to reduce future transaction costs, while increasing the impact of the resources allocated, within the perspective of desired visions and objectives. The multi‐actor platforms derived from the project emerged through bottom‐up processes, empowering landscape actors and ensuring, to a certain extent, the influence and long‐term impacts of the process they facilitate.

Ways and means of articulating local development and climate change adaptation

The project name in Spanish, agreed upon by the local project partners, is Climate change adaptation for local development,but experience shows that the relation is also the other way around: Local development for climate change. As a matter of fact, the main driving force for local concerted action has been so far to resolve immediate felt and shared local development needs such as securing access to water, food, health and livelihoods. These, however, also contribute to strengthening local capacity to adapt to future changes. Hence, the relationship between the goals of climate change adaptation and local development is not linear but interactive, in tactical and practical terms. This needs to be a central approach in the overall climate change plan (and pilot action) to be elaborated in every Model Forest.

Scaling up initial local action for policy debate and impact

When initiating collective action around perceived needs, people want to be successful and tend to deepen their understanding and widen their horizons, which helps tackling more complex matters, and motivates and enables people to fully participate in political debate and engage in advocacy.

We find a clear example of this in the Aracaurias del Alto Malleco Model Forest, where political influence was a strong driver of the local team to take part in EcoAdapt in the first place, and where this desired effect can be clearly observed today: actors in the two communities are more knowledgeable on water affairs, locally and nationally, they get in touch with political representatives and join the movement to bring about some desired changes in the water policies and legal framework. This is entirely in line with the Chilean Laws of Transparency and Citizens Participation in Public Affairs.

The challenges of improving water governance and managing conflicting interests and views

It is essential to improve water governance and create more effective and fairer rules of the game with regards to access, use and the distribution of increasingly scarce water resources. Our final analysis indicates that good governance and watershed management are critical for sustainable climate change adaptation.

Water (scarcity) can be both a source of conflict and cooperation depending on the institutional arrangements and rules of the game. This is crucial to consider in view of increasing water demands by different users and uses and diminishing water supply caused by climate change. The fear of future conflicts around water was one of the reasons to select water and watershed ecosystem service (WES) as the central topic of the EcoAdapt Project. Still, conflict is not necessarily an outcome of climate change. Conflict around water could actually arise due to a myriad of other stressors that converge in the Model Forest landscapes, such as increased water demand and pollution. It is therefore important to consider multiple drivers of change and analyze in which conditions and how the outcome could lead to cooperation rather than conflict intensification.

To enable fruitful debate and decision‐making on burning issues such as governance, rules of the game and channeling conflicts of interest and views about water use, it is advisable to create first a sound basis of trust and cooperation around joint action in less conflictive matters. To this end, stakeholder mapping and analysis is useful to identify synergies or conflicting interests, and identify entry points for action.

Looking backward and forward on the path towards the project vision

One of the challenges of connecting local development, political debate and policy‐making is to reconcile the immediate goal of satisfying the felt needs of local actors with advancing towards more complex and demanding changes, at higher levels of social aggregation. According to our experience, this is possible through an adaptive strategy. The original roadmap needs to be consulted and updated constantly in light of new findings and reflections and links must be established with the communities and policy‐makers from different levels of government.

During a project’s lifespan it is fundamental to lay down the groundwork in terms of motivated, informed, committed and collective cooperation and organization within the three Model Forest areas. It is also essential to start addressing and tackling some burning issues such as governance, regulations and conflict management around water access and use, which are fundamental for achieving sustainable climate change adaptation. This can be achieved through promoting clear thinking and informed action.

Full clarity and certainty on certain issues does not necessarily have to be reached in order to start acting, because this would lead to a state of paralysis. Clarity and certainty can be achieved through a process of acting-learning‐readjusting, as shown by the literature and experiences in adaptive management. In such circumstances, the goals of change must be clearly defined, as well as the objectives of learning and inquiry, if possible with a working hypothesis and small‐scale pilot actions which will shed light on the road ahead. This is the essence of adaptive management, of the wheel of learning and of action‐research. This approach is even more important when one enters into a new, unknown thematic area, to be further explored and discovered.

Enabling Factors

Learning through the project was initiated through a dynamic process that is already showing positive results, including growing commitments and capacities among the local actors in the three EcoAdapt Model Forest areas in Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, respectively. Interestingly, and in contrast with the project’s initial strategy to integrate climate change adaptation into local development, focusing on water security and local development turned out to be a better starting point for collective action and learning than climate change.

Multi‐actor platforms were fundamental in generating a learning process which stimulated in turn further learning processes. First, a series of knowledge‐sharing workshops were held which resulted in a permanent path of joint learning and engagement. These workshops highlighted the demand for more precise and accessible information which led in each Model Forest to the formation of platforms of multiple “change agents” helping to organize field learning activities. These activities generated some promising outcomes, for example, a common interest and understanding of water as a core component of the watershed ecosystem, and improved awareness of the importance of the community drinking water systems, particularly with regard to physical infrastructure, local management and governance.

Through a broad representation of local groups, these multi‐actor platforms achieved a growing legitimacy in their respective local environments, filling a niche by addressing felt needs for local development around water issues. Other positive effects included the mobilization of human, institutional and financial opportunities and resources, an enhanced debate on dissemination of relevant information, and growing trust among actors through a common language and vision. All this contributed to lowering the barriers between groups and institutions, and reducing future transaction costs. In the long run, this could decrease operational costs and help the community to be more effective in its actions around different issues related to water management.

In addition, the learning outcomes or lessons learned are converted gradually into inputs for strategic development, scaling up, outreach, policy debate, and policy implementation. Distances between the actors diminish; policy‐makers get more involved; people become more knowledgeable concerning legal and policy matters and are willing to try to influence these policies or to make better use of them. Improved understanding of water issues and the need for joint action go hand in hand, while the levels of intervention can be better integrated, leading to increased impact.

View more EcoAdapt project outputs:

EcoAdapt Project: Cross-site Analysis of Ecosystem Based Adaptation in South America

Barreras, fortalezas y oportunidades para la adaptación basada en ecosistemas: Bosque Modelo Jujuy

EcoAdapt project – Working paper on social dynamics during adaptation planning

EcoAdapt project: Lessons Learned from the Analysis of Socio-Ecological Dynamics

EcoAdapt project: Socio-institutional context analysis

EcoAdapt project – Working paper on social dynamics during adaptation planning

iModeler manual: a quick guide for fuzzy cognitive modelling

Cronología de los cambios en el paisaje de la región de la Araucanía desde 1850 hasta 2013

Suggested citation:

Prins, K., Cáu Cattán, A., Azcarrúnz, N., Real, A., Villagron, L., Leclerc, G., Vignola, R., Morales, M., and Louman, B. (2015) Creating and Sharing New Knowledge Through Joint Learning on Water Governance and Climate Change Adaptation in Three Latin American Model Forests: the EcoAdapt Case, IUFRO Occasional Paper 30, IUFRO, Vienna

(0) Comments

There is no content