SDC Climate change foresight analysis 2020: Global and regional risks and hotspots

Introduction

Update available: Read the 2021 update to this foresight analysis.

Climate-related risks and hotspots are a result of a combination of climate change and variability, exposure and vulnerabilities of people and ecosystems and their ability to address those risks (readiness, adaptive capacity, etc.). Understanding them is essential to delivering projects and programmes that increase climate resilience and result in interventions fit for coping with climate change risks.

This foresight report* provides information about short- and medium-term climate-related risks that might influence the programme and strategic work of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and analyses these risks with regard to water, food, health and regional stability with a focus on short- and medium-term projections of 1–3 years. The report is the result of strategic reflections from SDC’s Global Programmes Climate Change & Environment andFood Securitytogether with representatives of humanitarian aid and the different geographical units responsible for bilateral aid, on how SDC will increase its efforts to contribute to climate resilience in all its working areas in the future. While the report was produced for SDC, the analysis might be relevant to other organizations and actors undertaking work relating to sustainable development.

The study is based on and reflects publicly available scientific information that was available at the end of 2019 – it thus does not reflect the latest climate-related phenomena such as for example the recent locust outbreak in East Africa or the expected social and economic implications of COVID-19 that are likely to have an impact on many of the underlying drivers of vulnerability.

*download the full report from the right-hand column. A summary of the approach and key findings is provided below. See the full report for a detailed analysis of regional climate risks and hotspots.

Assessing global risks and hotspots

The report provides a summary of current and future global risks and hotspots and a rough analysis of regional risks and hotspots relating to climate, food, water, human health and regional stability for:

- Middle East and North Africa

- East and Southern Africa

- West Africa

- Western Balkans and new EU member states

- South Asia and South East Asia

- Central Asia and South Caucasus

- Latin America and the Caribbean

Key findings of the report

These are the key findings of the report. For a more detailed analysis of regional climate risks and hotspots see the full report.

Current global risks and hotspots

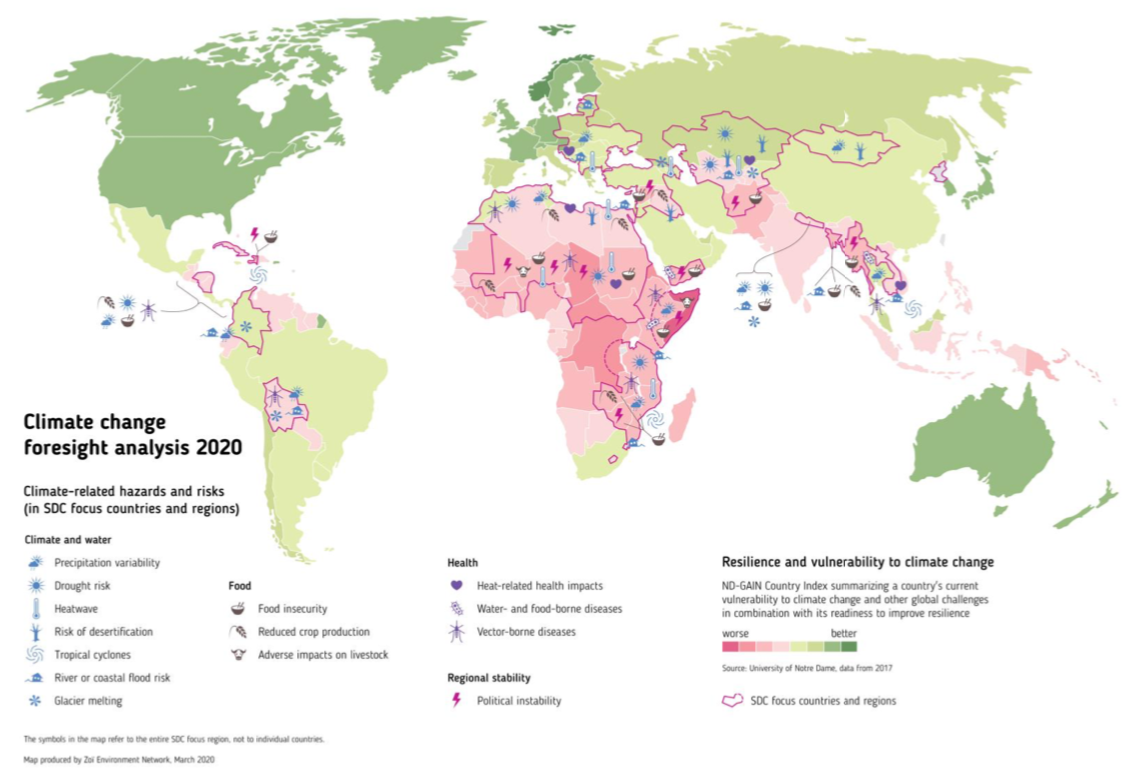

Figure 2 (see main image, above) gives an overview of the current climate-related risk situation in the world, based on the ND Gain Index. The ND Gain Index measures vulnerability including exposure in life supporting sectors – food, water, health, ecosystem services, human habitat and infrastructure – on the one hand, and economic, governance and social readiness on the other hand. The map in Figure 2 indicates the most relevant hazards and related impacts in SDC focus countries and regions identified in this analysis.

Hotspots with high climate-related risks are identified in large parts of sub-Saharan Africa (in particular the Horn of Africa and parts of the Sahel region), Syria, Yemen, the Hindu Kush, Bangladesh, Myanmar and Haiti. Those areas show interlinkages between various climate-related and non-climatic stressors, and a high vulnerability in all life-supporting sectors. The analysis of areas with currently high climate-related risks observes the following.

- Arid and semi-arid areas are extremely vulnerable to climatic trends. Where agriculture (crops or livestock) is the predominant livelihood activity, food systems entirely dependent on rainfall, and to a lesser extent irrigation-based systems, in water scarce areas are at risk. Such conditions can be found in large parts of the world, in particular in the Sahel region, in large parts of East and Southern Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, Central Asia and Central America.

- Low-lying coastal areas and cities are prone to coastal hazards and sea level rise. Given the high population densities in many coastal areas and growing urban populations, exposure and hence the risks are particularly high and increasing. This is the case for Bangladesh, coastal areas of Myanmar, parts of East and Southern Africa (Mombasa, Dar-es-Salaam, Maputo), the Nile delta in Egypt and Haiti.

- High mountain areas and downstream areas where the role of the cryosphere is important for water resources are strongly affected by glacier melt. As melt rates increase, run-off will also increase until a certain point – peak water – when the glacial mass is reduced to such a degree that run-off will start to decline. Peak water has likely already been reached in the Caucasus and parts of the Andes and is a future concern in Central Asia (the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers are mostly fed by snow melt and glacier melt) and the Hindu Kush.

- In regions affected by compound or sequential events – such as severe drought followed by extreme rainfall or the sequential occurrence of several hurricanes – risks are particularly high. Compound or sequential events cause extreme impacts in natural and human systems. Droughts followed by floods were reported in the last two years in parts of East and Southern Africa (Sudan, Somalia, Burundi, Madagascar, Mozambique, Malawi, Eswatini, Djibouti, Zambia and Zimbabwe) and in Syria in 2018. In March and April 2019, Mozambique was hit for the first time by two major tropical cyclones in the same season (Idai, Kenneth). In 2017, the above-average hurricane season led to the sequential occurrence of Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria on the Caribbean and southern US coasts.

- Countries with persisting conflicts often have high climate-related risks, given that climate has complex interaction with various drivers of conflicts and instability (water scarcity or food insecurity). High political instability may further affect people’s ability to cope with possible future climate shocks. Conflicts persist in Yemen and Syria and to minor extents in parts of the Sahel (Lake Chad Basin, Central Mali).

- Long-term unsustainable resource management practices, overuse of scarce land and water resources, environmental degradation and increasing demand due to population growth are putting pressure on natural systems and are strongly influencing current climate-related risks. In almost all regions with high climate-related risks, non-climatic drivers have a stronger effect on current risks than climate variability and change. Examples include the drying out of the Aral Sea, large-scale deforestation in the Amazon region or the depletion of aquifers in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

Future global risks and hotspots

Assessing short- and medium-term climate-related risks is challenging, as no specific weather or climate predictions can be made with a time horizon of 1–3 years (see Annex 2 of the report for methodological details). Nevertheless, some estimates about short- and medium-term risks can be made by analysing current risks and developments.

- Short- and medium-term risks are dominated by the current risk landscape.Climate risks are a result of the combination of climate hazards, exposure and vulnerability. While the climate signal – the occurrence of climate hazards or events in the next 1–3 years – is uncertain, exposure and vulnerabilities as key determinants of risk either do not greatly change from year to year or the changes are more predictable. Furthermore, non-climatic drivers have a stronger effect on current and short-term future risks than climate variability and change. Hence, we can assume that the current risks and hotspots strongly influence the risk situation in 1–3 years.

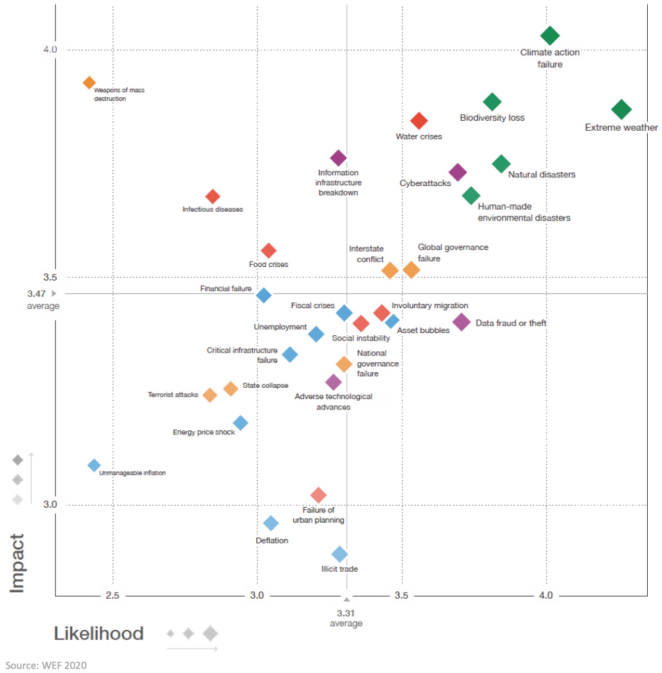

- Perception of risks is an indicator for potential upcoming risks.The perception of risks has a forward-looking perspective, as it gives an indication of risks or threats that are likely to occur in upcoming years. Environmental risks dominate the results of the World Economic Forum Global Risks Perception Survey for the fourth year in a row. In 2020, for the first time in the history of the Survey, environmental concerns dominate the top long-term risks by likelihood, and three of the top five risks by impact are also environmental (see Figure 3, below).

- The latest survey shows that climate action failure and extreme weather were the risks of greatest concern. Other topics with strong connections to climate conditions such as natural disasters or water and food crises rank increasingly high in terms of impact and likelihood. As environmental risks occur with increasing frequency and severity, the impact on global value chains is likely to intensify, weakening overall resilience.

- Severe impacts of current extremes are affecting risk in the short term.While past or current climate extremes or variability do not necessarily influence the situation in 1–3 years, there is evidence that past or current extreme events with severe impacts have implications for short-term risks. Extreme climate events push a system to near or beyond the ends of its normally observed range. Extremes can be very costly in terms of loss of life, ecosystem destruction and economic damage, and have long-term effects as they increase vulnerability in upcoming years and decrease the ability to cope with future shocks. Droughts and droughts followed by flood in the Sahel and in parts of East and Southern Africa in 2018 and 2019 decimated livestock and destroyed farmland, negatively affecting people’s livelihoods for several years. In Haiti, hurricanes such as Dorian in 2019 affected the recovery process from previous events. Two major cyclones in Mozambique in March and April 2019 may also have long-term negative effects.

- Gradual changes continuously increase risk.For changes related to slow onset events such as sea level rise and glacier retreat, we can interpolate the same or faster pace in the future, and implications for 1–3 years out are very likely. Hence, gradually increasing risks are likely in low-lying coastal areas and high mountain and downstream areas where water resources depend on the cryosphere (see chapter 2 of the full report).

- El Niño is an important driver of climate variability.El Niño is the most important driver of climate variability and can trigger extreme weather events and disasters in various parts of the globe. Many of the vector-borne and waterborne diseases in several regions are sensitive to changes in weather patterns brought about by the El Niño phenomenon. New models allow forecasting an El Niño event about one year ahead, but not its duration and strength.

Suggested Citation

Steinemann, M., Guyer, M., Reutimann, J., Rüegge, B., and Füssler, J. (2020)SDC Climate change foresight analysis: Global and regional risks and hotspots. INFRAS: Zurich

Related resources

- SDC Global Programme Climate Change and Environment Division

- SDC Global Programme Food Security Division

- The World Economic Forum Global Risks Report 2020

- Climate Change & Environment Nexus Brief: Fragility and Conflict

- Climate Change & Environment Nexus Brief: Migration

- Climate Change & Environment Nexus Brief: Health

- Climate Change & Environment Nexus Brief: The El Niño Phenomenon and Related Impacts

- Shaping the water–energy–food nexus for resilient mountain livelihoods

- Addressing the Land Degradation –Migration Nexus: the Role of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification

(1) Comment

“Floods, Droughts, Cyclones, Earthquakes, Tornadoes, Heatwaves, Village fire, lightening, Distressed Migrations, trafficking Extremists Environmental Hazards,, ”: What Next?

Odisha in East coast India, unfortunately, is in the pathway of depressions and cyclones formed in the Bay of Bengal during the south-west monsoon. With the advance in global warming and climate change if sea storms acquire greater destructive power as is being forecast, the state will be required to bear the brunt of such storms which means all the gains of development will be washed away in flood/storms water.

The extremity of the degree human and natural disasters and implications of poverty is experienced by the situation that forces the people to live within a constant state of impoverishment, in circumstances where their most basic human rights, justice, entitlements need to rethink.

The operational strategies would be as follows:

To develop long-term vulnerability-mitigation strategies to reverse the ill effects of repeated droughts/disasters and break away from the vicious circle.

To create a coalition of multi-stakeholders (NGOs, CBOs, corporate, government and PRIs) and effectively interacting with the government departments to ensure continuous community level.

To institutionalize an information flow through organizational networking. Thus networking, coordination and convergence will be the highlight of the project strategy.

A participatory and decentralized monitoring process will be the highlight of project management

Knowledge Transformation and incubation, innovation, inclusion and incorporation of technology with appropriate demonstration, linkage establishment with culture-nature-water-ecology-economy-enterprise