The impacts of climate change on food security and nutrition in the Middle East and North Africa

Introduction

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA)* is host to some of the most challenging settings in the world for addressing food insecurity. MENA is the only region outside of Sub-Saharan Africa where the number of undernourished people has increased since the early 1990s, and is the only region where the proportion of undernourished people has increased. The region1 includes some of the world’s wealthiest countries and also some of the most fragile and least developed. This disparity creates sharp contrasts. 33 million people lack access to adequate nutrition and 18% of children under the age of 5 are developmentally stunted, yet obesity is also a growing public health problem.

This picture of varied food security and wealth is set against a backdrop of other development challenges. There are high rates of urban and population growth in many countries, increasing demands for scarce water, changing patterns of markets and provision of government services, pressures to sustain economic growth and create jobs, and political and security challenges. These – and other factors – all affect food security. Collectively they also pose both risks and opportunities for sustainable development in MENA countries.

Climate change will make these challenges even harder to address. Climate risks expose existing weaknesses in food systems, and add further complexity and uncertainty to decision-making. Departing from a broad food security and development perspective, this report sets out the risks to food security in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) from climate change, and how these vulnerabilities interact with other key trends and sources of risk, including population growth, urbanisation, and conflict. Focused on the policy relevant medium-term time horizons of 2030 and 2050, this report contributes to a better understanding of how these trends and risks may affect achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Zero Hunger in the MENA region. It highlights some particularly vulnerable groups, and also options for reducing climate risks to food security. Most studies in the region have focused on climate risks to food production. By contrast, this report emphasises the importance of climate risks to other aspects of food security, particularly people’s ability to purchase the food that leads to a safe and healthy diet.

*For the purpose of this report, MENA is defined as Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, West Bank and Gaza, and Yemen.

Download the full text from the right-hand column. The key points for policy makers and conclusions (abridged) are provided before. See the report for much more detail. Also available in Arabic – see the Further Resources section.

In the report

This report provides a comprehensive overview and discussion of:

- Current food security in the Middle East and North Africa

- The future climate of the Middle East and North Africa

- The impacts of climate change on food security

- Options for building resilience and reducing risk

Key points for policy makers are provided for each chapter – see the full text for more detail.

Conclusions

Climate change presents risks to the whole food system, from production through distribution and to consumption. However, climate change should not divert attention from fundamental food security and development objectives, and achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Instead, mainstreaming climate risk management into food systems can help address underlying vulnerabilities, weaknesses, and risks from other sources. By seizing the imperative to adapt, the challenge of climate change can be an opportunity to reform and strengthen food systems and food security, and also the human security, stability, and longer term sustainable development of the region as a whole.

-

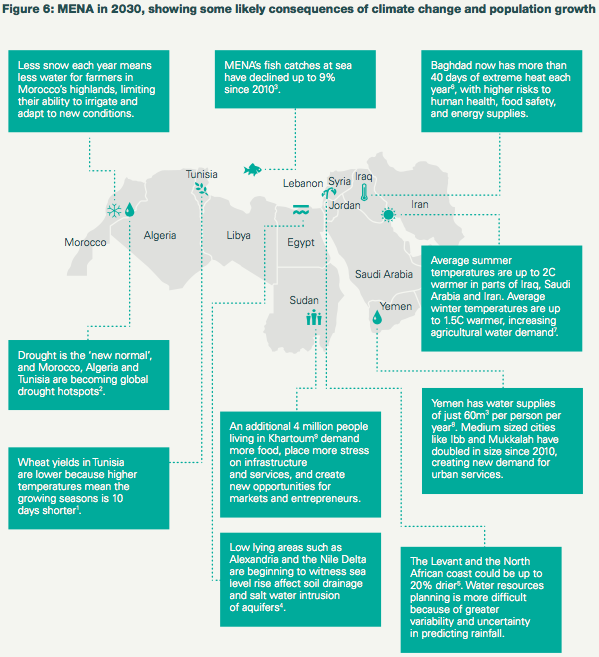

By 2030 climate change in MENA will be noticeable. Summer temperatures will be 1-2C warmer on average, and heat waves will be more common and more intense. 156 million people were affected by drought in MENA between 2000 and 2010, and by 2030 severe droughts are likely to be more common in the Mediterranean area, particularly in the Maghreb.

-

Already vulnerable and food insecure populations are a particular group of concern, as they are likely to be more susceptible to climate impacts. However, climate change is just one dimension of change that will affect people’s food security by 2030. Economic change will drive employment, income, and people’s ability to purchase food. Rapid urbanisation will change patterns of what food people eat, and how and where they get it. Protracted crises, conflict, and the fragility of states may also drive migration and patterns of food insecurity. By 2030, without reform of water management, higher competition for water is likely to severely affect poor people, with implications for their food production and food safety. Climate change will interact with other these other transitions, resulting in changing patterns of vulnerability and food insecurity.

-

More attention is needed on climate risks to access, stability and utilisation dimensions of food security. These are complex and less well understood than risks to food production and availability, but in MENA, are at least as important. Ensuring access to affordable and nutritious food for all people should be at the centre of efforts to improve food security. Poor farmers have a specific set of risks, as their ability to purchase food depends on income from crop yields that may be affected by climate impacts. However, the food security of an increasing majority of people is conditioned by factors such as food prices, not the availability of food.

-

By 2030 farmers of some crops in certain regions will see changes in temperatures and precipitation affect crop yields. Droughts will have more frequent and widespread impacts. Those with fragile farming systems unable to cope with higher levels of risk will be most affected. Small producers in remote areas of marginal lands – particularly uplands and drylands – are most vulnerable to climate risks due to fragile natural resources, low incomes, limited access to markets and government services, and the risk of being caught in poverty traps.

-

Climate risks to the food security of poor rural producers can be reduced by helping them:

- cope with droughts through improved programmes that anticipate and reduce the impact of shocks and help affected people recover quickly;

- increase farm productivity and income despite increasing temperatures and water stress, by improving access to appropriate techniques and technology, and to markets, services, and financing; and

- diversify away from agricultural production and adopt new livelihood activities.

-

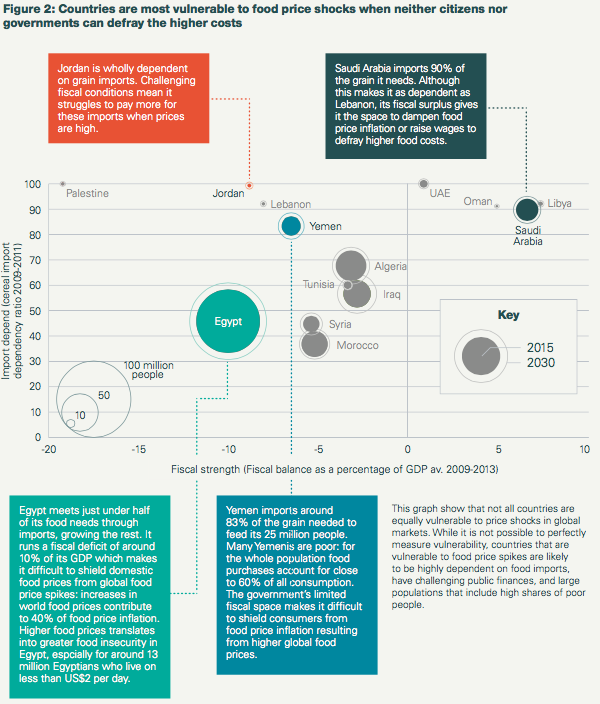

Most people will not be directly affected by climate risks to domestic agriculture. Their food security is much more closely linked to systemic risks such as changes in global markets, and how well their governments respond to shocks such as global food price volatility due to widespread harvest failure. Poor consumers in remote rural areas and rapidly growing informal urban areas are likely to be most vulnerable, due to low incomes and access to markets, and weak provision of basic services.

-

Climate risks to the food security of poor food consumers, particularly those in informal urban areas and remote rural areas, can be reduced by:

- addressing climate vulnerabilities in employment and income, such as impacts on infrastructure and labour productivity;

- increasing access of the poor to social protection systems resilient to food price volatility; and

- improving food safety, including food storage and provision of improved water and sanitation.

-

Looking at food security through a climate change lens adds to the calls for governments to improve risk management in general. In particular risks related to food import dependencies can be reduced to ensure food is accessible to poor people. Enhancing social safety net infrastructure must remain a priority to address the needs of the most food insecure people.

-

Strengthening supply chains, including supporting integrated systems of food storage, distribution and retail in MENA will offer significant opportunities for managing climate risk and reducing post-harvest losses. Ensuring cold storage and refrigeration of food during heat extremes and reducing risks at bottlenecks in exposed storage and transport infrastructure could all reduce vulnerabilities to the food security of large numbers of people.

-

Support is needed for action by a broad range of stakeholders, including governments, international organisations, academia, civil society, and the private sector. Finance and political leadership is required for making specific investments and reforms, and also for long term strategic planning and ensuring cross- sectoral coordination. Different sources of finance will be needed, including from the private sector and mechanisms for international climate adaptation finance. The Sustainable Development Goals provide an important framework for these streams to come together and strengthen the food security of the most vulnerable and at risk populations in the MENA region.

Authors

Guy Jobbins and Giles Henley, Overseas Development Institute

Suggested citation

Jobbins, G., & Henley, G., 2015. Food in an uncertain future: the impacts of climate change on food security and nutrition in the Middle East and North Africa. Overseas Development Institute, London / World Food Programme, Rome

Funders

This publication is made possible through the generous contribution of the Government of Sweden and the Climate Adaptation Management and Innovation Initiative (C-ADAPT).

(0) Comments

There is no content